How to Celebrate Your 70th Birthday--Part II: Our Trip to Santa Fe

I can’t count the number of times that I have visited Santa Fe. My older sister and family lived in Albuquerque for some time, and when I was a kid we would visit with them and sometimes drive to Santa Fe and to surrounding American Indian Pueblos to attend Indian feast days and ceremonial dances. I developed a love of those cultures and also of Mexican food on those visits to New Mexico. (This was well before Mexican food restaurants had spread all over the country.) Later, while stationed in the army and living at White Sands Missile Range, outside of Las Cruces, I became familiar with much of the state, including Santa Fe. In my early visits, Santa Fe was already an artists’ haven, but it did not have the hot appeal that it does today, with the real estate prices driven ever higher by the number of wealthy people settling there or buying second, vacation homes. Now the town can take its place with hoity-toity Aspen, Carmel, Park City, Jackson Hole, and Sedona as one of the in-places to visit. This change does not make it better, but I still love it. It is no wonder that people want to move there. It is now called “the City Different” with its predominant adobe style, low lying buildings and homes and its intersection of three main cultural groups—Native Americans, Hispanics, and European Americans (in New Mexico usually called “Anglos”).

On one visit I attended an academic conference in Santa Fe and met my two older sons there—Christopher and Steven. If truth be told, I never made it to the conference, but we did make it to Taos Ski area and ate a lot of Mexican food. And Beth and I had together visited Santa Fe twice in the past. Let me give you a flavor for the City Different that we experienced on our visit before this one. When we first arrived at the downtown plaza we were stopped by a parade that circled the plaza square several times. The parade consisted of three units: first came a marching band in full red uniforms; the band was followed by a boy scout troop marching along, also in full uniforms; and the last unit was a local chapter of the Shriners, all wearing red fezzes and riding go-carts. As they circled the plaza, they did intricate formations and weaved in and out on their go-carts. And then the parade was over. We stood awe-struck and dumb founded. What could this small assortment of parade units possibly represent? We never learned. People seemed to take it in their stride and continue on with their lives.

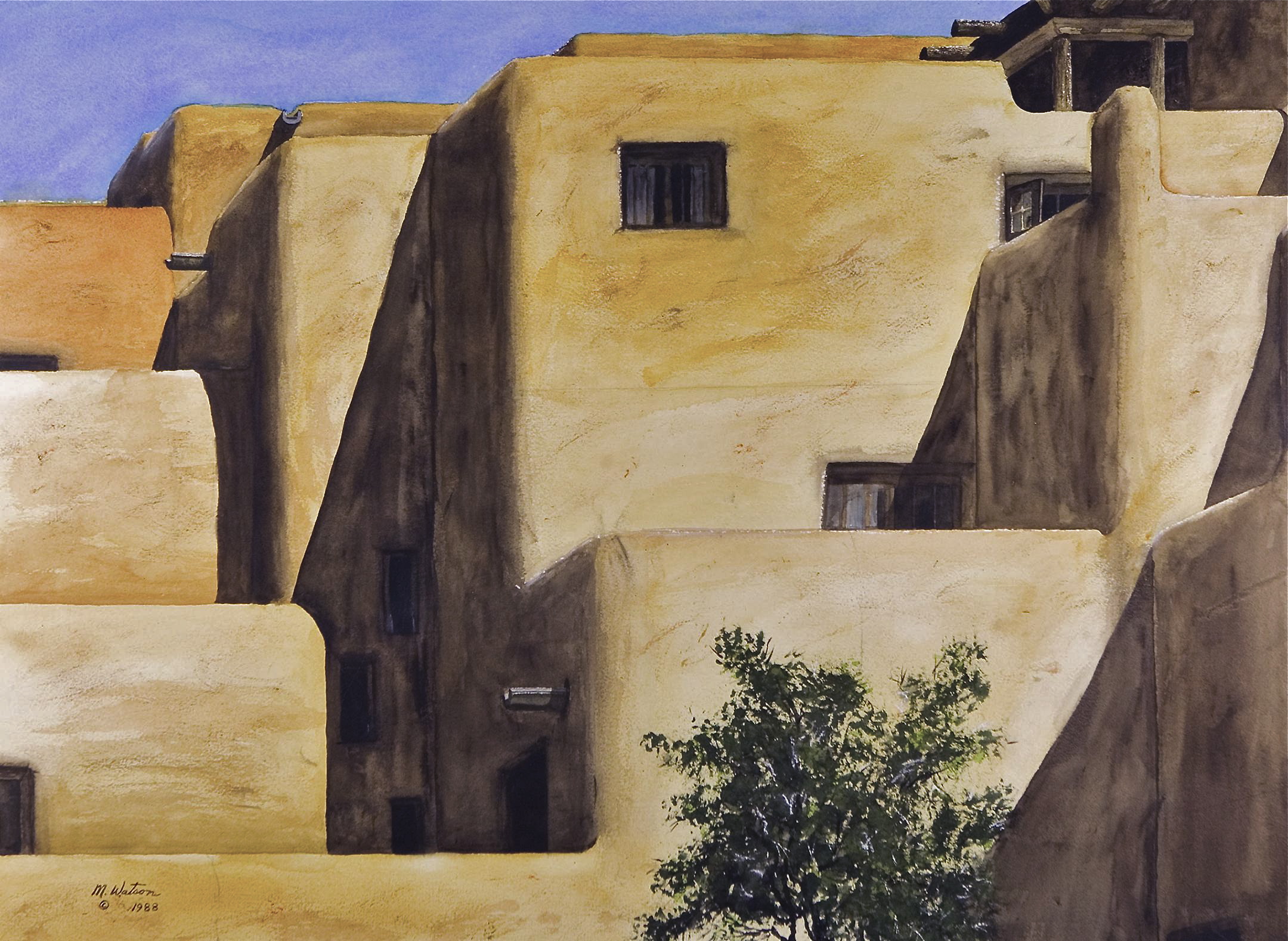

On this current visit in early January, 2014, we flew into the Santa Fe Airport after dark (the first time I had ever arrived via that airport). It had only one gate and two taxi vans to pick up travelers. We drove through the high, flat desert, the myriad stars shining brightly in the black sky overhead, until we reached the city. We stayed at the Inn at Loretto, in a building I love and had painted in the past. Now I finally had the opportunity to stay there. The inn exhibited art work all over the walls of the long, winding, maze-like hallways. As we were led to our room, I could hear voices down the corridor and I thought I heard them say, “Welcome to the Hotel California.” We decided not to eat in the main dining room because we were afraid that, though we stabbed it with our steely knives, we just could not kill the beast. And what hotel restaurant serves live beasts anyway? (No, just kidding; I didn’t hear any voices down the corridor, but it did remind me of that other hotel, and for awhile I thought I could never leave. I got lost in the corridors several times trying to find the elevator down to the main floor.) Our room was southwestern and funky, with vigas in the ceiling and a corner, adobe fireplace, as I had wished for. The inside of the building had as many nooks and crannies as the outside did. (Compare the photo of the building as it looks today and as I painted it some years ago.

The Loretto Inn is so named because it abuts the Loretto Chapel , made famous by a mystical spiral staircase built without supports in a few days by a stranger who came through town and decided the nuns of this chapel needed stairs to the choir loft (they had been using a ladder).

A Brief History of Santa Fe

Before I continue with my description of our visit, it may be of interest to provide a brief history of this old town—the City Different.

First, there were many Native American, pueblo villages in and around Santa Fe, probably dating back to about 900 A.D. The Pueblo Indians had always been peaceful, farming, village dwellers who built their homes, apartment style, of adobe bricks covered with mud and straw mortar, an entirely appropriate method for the area, as the adobe kept the homes cool in the summer and warm in the winter. Apparently, the Spanish came up from Mexico primarily to discover gold that was rumored to be in these villages. Perhaps people were deceived by the gold color of some of the pottery or by the sun reflecting off the golden tan homes.

In 1598 Don Juan de Onate established a Spanish capitol for the region in Santa Fe. As more Spanish moved in from Mexico, with their heavy-handed conversion techniques, they made life more and more intolerable for the natives of the region—the Puebloans. They forced conversion to Catholicism; they took them as slaves, sending many back to Mexico; they made them pay tributes for the churches they built and for the government; they took over the best farmland; and they established absolute theocracies for their governments. It should come as no surprise that, though the Puebloans were generally a peaceful lot, there were some uprisings. After one particularly bloody rebellion, the Spanish authorities outlawed all practice of any religion except the Spanish brand of Catholicism and amputated one foot of each man whom they found practicing his native religion.

The situation went from bad to worse, and finally a man named Pope from San Juan Pueblo (which has now returned to its native name of Ohkay Owingeh) organized a revolt of all the pueblos. This has become known as the “First American Revolution.” He started planning the revolt at Taos Pueblo, to avoid the capitol at Santa Fe where the majority of the Spanish were living. He sent runners to all the pueblos and through a secret communication system organized the day of the revolt. On August 10, 1680, Puebloans throughout the region killed about 400 Spanish settlers, stole their horses so they couldn’t flee, and then sealed off the roads leading into Santa Fe. All the Spanish settlements except Santa Fe were destroyed. They then laid siege on Santa Fe and cut off their water supply. About 2000 Spanish were holed up in the Palace of the Governors on the Plaza and eventually negotiated a retreat back to Mexico. After this revolt, the Puebloans destroyed the Catholic churches, restored their native religions and had cleansing baths to purify themselves from the Spanish influences.

However, this new found freedom was short-lived. In 1692, the Spanish came back with a vengeance and carried out a bloodless re-conquest of all the pueblos except Hopi in Arizona. Though there were a few minor revolts, the Spanish conquered all, but they did not again attempt to establish a theocratic government or outlaw all native religions Ever since that time the two cultures have been learning to live together, along with the new interlopers—those of the Anglo culture. Today, the region is one consisting of three cultures that most of the time work together and get along, though there are still large differences in wealth and educational opportunities. Recently, the Santa Fe Indian School (now run by Indians to help preserve their own cultures as well as educate their children in main-stream subjects, unlike the Indian schools of the past, which tried to destroy native cultures) put on a play about the 1680 revolt. (We talked to a man whose children went to the school and were involved.)

Moving forward in time, in 1836 the Republic of Texas claimed Santa Fe as one of its capitols, but by 1848 Santa Fe was claimed by the United States. In 1851, a Catholic Bishop—Lamy—came to Santa Fe and built the St. Francis Cathedral right off the plaza. In 1912, a movement was begun to beautify and modernize Santa Fe and make it an art and tourist center. In the process, they passed ordinances to preserve and maintain the Puebloan, adobe building style, with the flat viga roofs, and to preserve the old streets and buildings. When the Santa Fe Railroad was built and later Route 66, an influx of American tourists came to the area, often to see “real Indians” and also to buy their arts and crafts. The Railroad station is a great reminder of that influence. In 1919, the annual Spanish Fiesta was begun, and in 1922, the annual Indian Market was initiated. These are today hot celebrations and markets for the arts and bring in people from all over the world.

And through all of this Santa Fe remains the oldest, continuously used capitol city in the United States, 1598 to the present—the City Different indeed.

The Art of Santa Fe

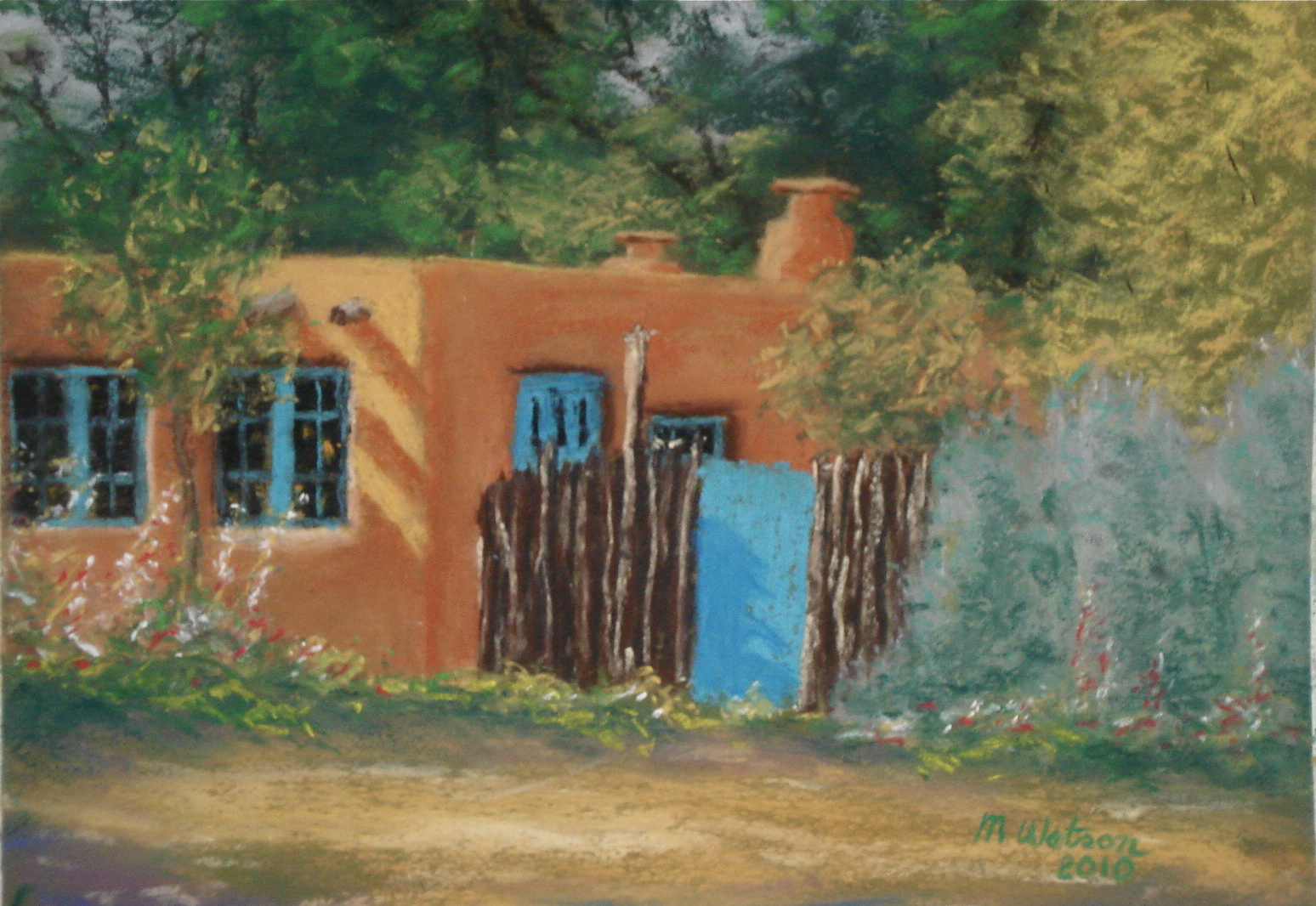

First and foremost comes the architecture. Although one might consider it all too much the same, there is something transforming in immersing oneself in the ubiquitous tan-brown buildings with their clean straight lines and recessed windows and doorways, many highlighted by blue or turquoise colored window and door frames. And while I am at it, let me mention that the blue skies in the high mountain air of Santa Fe seem to be deeper and purer than anywhere else. It is no wonder that artists have long flocked to the place and that turquoise is the favorite color. Here is one home I tried to capture in a pastel painting and then photos of some of the actual homes.

Our first day we strolled the length of Canyon Road, the epicenter of the art of this town. We went into many of the art galleries on that narrow, winding street. In Santa Fe, there are probably more art galleries per capita than in any other art mecca in the world, galleries that started out in the early years featuring southwestern and Indian art but now displaying a myriad of styles and types, from representational to abstract, from serious to whimsical and funky, from established and famous artists to new, emerging artists. Here is a sketch I made of Canyon Road.

We had a long conversation with one young woman who painted various animals in unusual colors, and we almost succumbed to buying one of her paintings of a deer done in green and orange with the most beautiful black eyes, but we held out. We also had a wonderful conversation with one of the owners of Manitou Galleries, William Haskell, who also painted watercolors on canvas, which he then varnished in such a manner that he could add wet paint over the watercolors without running the original layers. They indeed looked like watercolor paintings but they had an unusual sheen to them. I tried to figure out the process, but, even though he described it in detail while I looked at his paintings, it escaped me. I wish I could do it. He invited us to a special artists’ reception that night at their other gallery in the middle of town, off the plaza. We attended and there talked to several more artists. Tom Perkinson was an old cowboy, originally from Indianapolis who moved first to Oklahoma and then to New Mexico to obtain an MFA. In his paintings he started with a wash and scene done in watercolors and then finished them off with details done in pastels. He carefully explained the entire process as we viewed his paintings. Now here was a style I would like to try, using my two favorite media—watercolor and pastel. The third artist that we talked to was Don Weller, who started out raising horses in Washington State, then worked as a graphic designer in Los Angeles, and has since been living in Oakley, Utah, where I used to attend rodeos and go horseback riding. He paints beautiful watercolors of horses, cows, and cowboys, and he has created several paintings that have been used on U.S. postage stamps.

Regarding the whimsical art on Canyon Road, here is a wooden coyote that was prototypical. Beth and I did not discriminate between galleries exhibiting high art and those exhibiting funky stuff.

Along with all the western art, we decided we wanted to purchase some cowboy shirts for our boys, and for me. (I guess cowboy shirts can also be considered western art.) To our surprise, we had a difficult time finding stores that sold cowboy shirts. (We found plenty of stores that sold hand-made cowboy boots and belts, beautiful but in the $800 to $1000 range—forget that.) We did find one store that specialized in used cowboy shirts, often with the pearl buttons ripped off or tears in the sleeves. I think they were taken off dead bronco and Brahma bull riders in the rodeos. There was one item in a second-hand store that I wish now we had purchased. It was a traditional black tux with the traditional silky lapels. However, someone had painted with acrylics a large, white, steer skull on the back of the jacket, Georgia O’Keefe style, and another one on the pocket of the front of the jacket. It was outrageously beautiful, and I thought that Ethan might have enjoyed wearing it to his senior prom. The price was right, but, alas, we let it slip away without even capturing it in a photo.

While looking for things cowboy, we did run into a husband and wife team who ran a jewelry shop and may well have been a real cowboy and cowgirl. He certainly sounded like one, and he wore a cowboy hat and had long white hair and a long white goatee. He reminded me of old pictures of Buffalo Bill. She wore enough silver and turquoise jewelry to anchor her to the floor. We talked to them for some time about their life in the west and whether or not they were real cowboys. I came to the conclusion that they were, even if they did run a snooty jewelry store.

We also ran into this pool hall, which shows that in Santa Fe they celebrate cowgirls and well as cowboys.

My Guide to the Southwest Indians and their Pottery and Jewelry

I have to admit that I am addicted to many of the exquisite arts and crafts created by American Indians of the southwestern United States. As someone said, there is only a fine line between a hobby and an addiction. Because of my love of their arts, I began learning about their histories and cultures as well; then, I met some members of these groups and ended up having some of them, whom I now consider my friends, to Brandeis for some cross-cultural presentations. So I could go on and on, but I will try to keep this guide a reasonable length.

Background

There are three main groups of American Indians or Native Americans (they use both terms) in the Southwest (in New Mexico and Arizona). First are the Pueblo Indians, who almost certainly descended from the Ancient Puebloans, formerly called the Anazasi, of Mesa Verde, Chaco Canyon, and other surrounding cliff dwellings and ancient villages. Each pueblo group lives primarily in a tightly compact village, each on its own reservation. There are currently 19 pueblos in New Mexico, and though they share many cultural practices, they each have unique aspects and consider themselves to be separate (though related) tribes or groups. Some are particularly known for one art or craft and some for another. The Hopi of Arizona are closely related to the Puebloans of New Mexico and, I think, belong in that group as far as life style and beliefs and practices go. So that would make 20 tribes.

Second are the Navajos, mainly in northeastern Arizona. They are the most populous tribe in the U.S. and have the largest reservation in terms of land size. Though they have several towns on the Reservation (such as Tuba City, Chinle, and Window Rock), they tend to live separated from each other, probably because many of them still raise sheep (often with a summer and a winter home to allow for grazing). They are not related to the Puebloans except through modern-day intermarriage. The Navajos are strongly matriarchical and matrilineal in their families and community organizations.

Third are the Apaches, who live primarily in New Mexico but also in Arizona on several reservations. They were originally wanderers and hunters.

All of these groups show a great deal of courtesy when interacting with others. In their traditions, one does not make a lot of eye contact because that shows disrespect; one does not talk a lot because that shows disrespect; one does not touch another person or squeeze their hand tightly in a handshake, out of respect for their body and space. Women are treated with special respect and are often in charge in the family. So, you can see that main-stream Americans can unknowingly be discourteous and disrespectful in those cultures. However, these people would almost never mention these problems to you because that would be so disrespectful of you. So, contrary to my natural inclinations, when I am among these groups, I must refrain from talking so much and being so loud and barging right in.

The Arts and Crafts

Hand made Indian arts and crafts, when they are done well, are exquisite, beautiful works of art, are extremely labor intensive, and are great because they are at the same time individual and creative but highly traditional, being produced by ancient techniques. And, after all, they are made by American Indians. So, the good pieces are expensive and getting more expensive all the time, just as serious paintings and other works of art are expensive. (I actually don’t begrudge the artists for the expense. With the extreme poverty among these groups and the suffering that the U.S. government and greedy people have put them through, it is good to see that some of them can actually make some money.)

You can get imitations and cheap versions. You can even get stuff made in Asia. So be careful if you want genuine Indian made products.

Pueblo Pottery

The traditional pottery is made from clay dug by hand on the reservations and mixed with a temper of sand or volcanic ash and then painted with paint made from plants and minerals found on the reservation. The pottery is made by hand (hand built) usually using the coil method and then smoothed with scrapers made from pieces of gourds and sandpaper (potter wheels and molds are not used). The pots are then usually covered in a slip (liquid clay) and then hand polished (i.e., burnished) using tumble polished stones. No glaze is used. Then designs are either painted on or carved into the clay. Sometimes, a fine knife (such as an exacto knife) is used to cut fine and shallow designs into the clay (called sgraffito). The pots are then fired in outdoor fires, often using a particular kind of wood or sheep or cow dung to give the pot a particular color or look. Sometimes pots are finished off in an oxygen-reduction fire in which the oxygen is cut off by piling powdered dung onto the fire. When this is done the carbon infuses the molecules of the clay pot and turns it black. So a normally red pot can come out dark and shiny black. Sometimes parts of the fire or wood touch the clay and cause black patterns called fire clouds on the pot. Often these are done intentionally to get an artistic pattern. Sometimes more or less heat will turn the clay varying colors even on the same pot and thus create artistic variations.

The two most famous potters in the early 20th Century, who were responsible for making Pueblo pottery popular and seen as a serious art form, were Nampeyo of Hopi and Maria Martinez of San Ildefonso Pueblo. Although most of the Pueblos and the Hopis and now the Navajos and Apaches make pottery, the most and generally some of the best pottery is made by the Hopis, Acoma Pueblo, Santa Clara Pueblo, and San Ildefonso Pueblo.

I have about 40 pieces of Pueblo pottery. (I guess this is where the addiction comes in.) I usually don’t pay more than a few hundred dollars for one pot, but I now have several that have climbed in value and are worth more than $3000 each. So, as art goes, they were wise purchases. I think I know pueblo pottery well enough to know good work when I see it, and I look out for new or young potters who are good and have not yet been discovered. Then I can afford their pots. Like other art, the value increases as the potters (artists) achieve more acclaim and have their pieces in major museums around the world or win prizes at art shows. When we were recently in Arizona, I bought a piece from a young Hopi potter for $300—I loved the pot. Then he won a major award at an art show, and now his pots start at $700. The work of the best potters can reach $80,000 per pot. I don’t think you will find a decent piece of pottery for under $100. I personally won’t pay over $600, which means I really can’t afford the pieces that I would love to have. Here are two of my pots done in this traditional way, one from San Ildefonso Pueblo and one from Acoma Pueblo.

By the way, the outdoor fires used for firing these pots today don’t get them nearly as hot as would occur in a kiln. So this pottery is only for art; the pieces should not be put in water or used for food or cooking. A notable exception is the pottery hand built of mica clay by Felipe Ortega (Apache) and his students and sold at some cooking stores, such as the Café Pasqual Gallery in Santa Fe. These pots are high fired and strong and give a most wonderful taste to beans, stews, and food cooked in them. And they are unusually beautiful.

Jewelry

What would Southwestern jewelry be without silver and turquoise, but other stones and shells are commonly used as well. Turquoise has special meaning to most of the tribes and is thus seen as more than just a pretty stone. The best silver work comes from the Navajos; the best stone inlay comes from the Zuni Pueblo; and the best beads come from the Santo Domingo Pueblo. But keep in mind that turquoise reigns supreme. Beth loves turquoise and silver, and so she has a lot of this jewelry, some of it bought from Navajo friends who made it. She feels safe and blessed when she wears a Southwestern bear.

Our Purchases

For this trip, Beth and I each had a budget, mine to spend on pueblo pottery, Beth’s to spend on turquoise jewelry, as if we needed more pottery and more jewelry. And, alas, we did not stay within our budget. Here is my prize purchase: a hand coiled and carved pot by Sue and Tom Tapia of Ohkay Owingeh (San Juan) Pueblo (where Pope was from during the first American Revolution).

And here is Beth’s Navajo, concho belt with boulder turquoise and silver.

On this trip we discovered a new trend in the Native American arts and crafts stores. Many of them are now run by folks from the Middle East, and with these new owners comes a different way of doing business. Rather than items having a set price and the shopkeepers knowing the Native artists well, the new owners set exorbitantly high initial prices and then expect to bargain on each sale. Often the bargaining takes the form of the sales person throwing in extra jewelry or items to sweeten the deal. “If you take this pot for $1000, I will throw in this other pot as well and these two necklaces.” And the wheeling and dealing comes fast and loose. They often get aggressive and belligerent when you try to leave without making a purchase, and if you leave the store without making a deal, the shop keeper alerts his brother or cousin in the next store down that you are on your way and that these are the items you are interested in. They already know about you when you arrive. Because there is no set price, this bargaining can be financially dangerous for anyone who does not know the range of values for a particular artist’s work. This system of bargaining may be fun for some, but I prefer the places (often old-time trading posts) where the owners love talking to you about pottery or the work of various Native American artists and can tell you stories about them. Those vanishing, traditional places have shopkeepers who are just as hooked on this stuff as I am. They love what they sell and love to see a customer love the works as well. The new breed of shopkeepers seems to love the bargaining process, regardless of the products they sell. They don’t exude the same love of the art work. Well, what else can I say: buyer beware.

For great shopping straight from Native American jewelers, we looked at the items being sold by folks sitting with their creations along the portico of the old Palace of the Governors on the Plaza. These places are reserved for American Indians only. It is fun to talk to them, and we purchased a few items.

Native American Fetishes

We enjoyed looking for one other Native American craft—fetishes. Now when I say fetishes, don’t think of shoes or some other sexual fetish. These fetishes refer to stone or shell or wood representations of spirit animals that were traditionally thought to accompany and protect an individual. (Everyone in our family has a personal bear fetish, and Ethan has quite a few Native American carved animals. He once thought it would be funny to ask one of his close friends--a girl--if she wanted to come up to his room and see his fetishes and then observe her reaction. He never did this, however.) So here is how it is supposed to work. Every person has a personal spirit animal that will protect the person and imbue the person with special strengths or gifts. A person should pay attention to nature until the person finds his or her personal animal. It might be a badger or an eagle or a snake, but the most popular is a bear. In fact, I think that most everybody seems to claim a bear as his or her personal spirit animal and then maybe another one as well. (Nobody picks banana slugs.) Then the person looks around and finds a stone or some natural object that looks like the personal spirit animal and keeps that object as a fetish to help keep the spirit animal close. Some Indian groups, especially the Zunis carve fetish animals out of rocks and shells, and eventually they have become popular as arts and crafts items, which are sold to tourists and art collectors. There is one particular store in Santa Fe that I believe has enough carved fetishes for every person in the world, made in all varieties of all kinds of materials, some exquisite carvings and some rough and crude, probably the way they used to be made.

Beth is an animal lover supreme, and though dogs, cows, and pigs, in that order, are her favorites, these domestic animals don’t seem to be used as fetishes. Her favorite wild animal is the bear, probably like everyone else. (Beth would not have picked a snake, for example.) She owns many bear fetishes and bear necklaces; so she can always feel close to her spirit animal. Here is a photo of three of her bear fetishes: one a Zuni carving out of black jet (a hard kind of coal), one a Zuni carving out of turquoise (of course), and one, a polar bear, that I made and fired for her out of white, porcelain clay.

And here is my bear fetish that I purchased on this trip. It is a rough hewn bear out of basalt, made by a carver from Cochiti Pueblo.

In one store, while I talked to the owner about several old Nampeyo pots that he was selling (they were out of my price range), Beth talked to his wife and discovered that she had breast cancer and was in the middle of chemo therapy. Beth told her about her own bout with breast cancer and chemo. In the process the woman said that she had faith that her spirit animal, a bear of course, would help her through this difficult time. When the woman first learned that she had cancer, a black bear had come out of the forest and began visiting them at dusk and at night in their yard. The night before she went in for chemo, the bear had pooped on her front door mat (not a common occurrence) and had then returned often to the yard to look at her. The woman took this as a sign that the bear was her spirit animal and had told her so with her “gift.” Who knows, it did give the woman great strength, and Beth and the woman seemed to form a bond because of their shared illness and the common spirit animal.

The Food

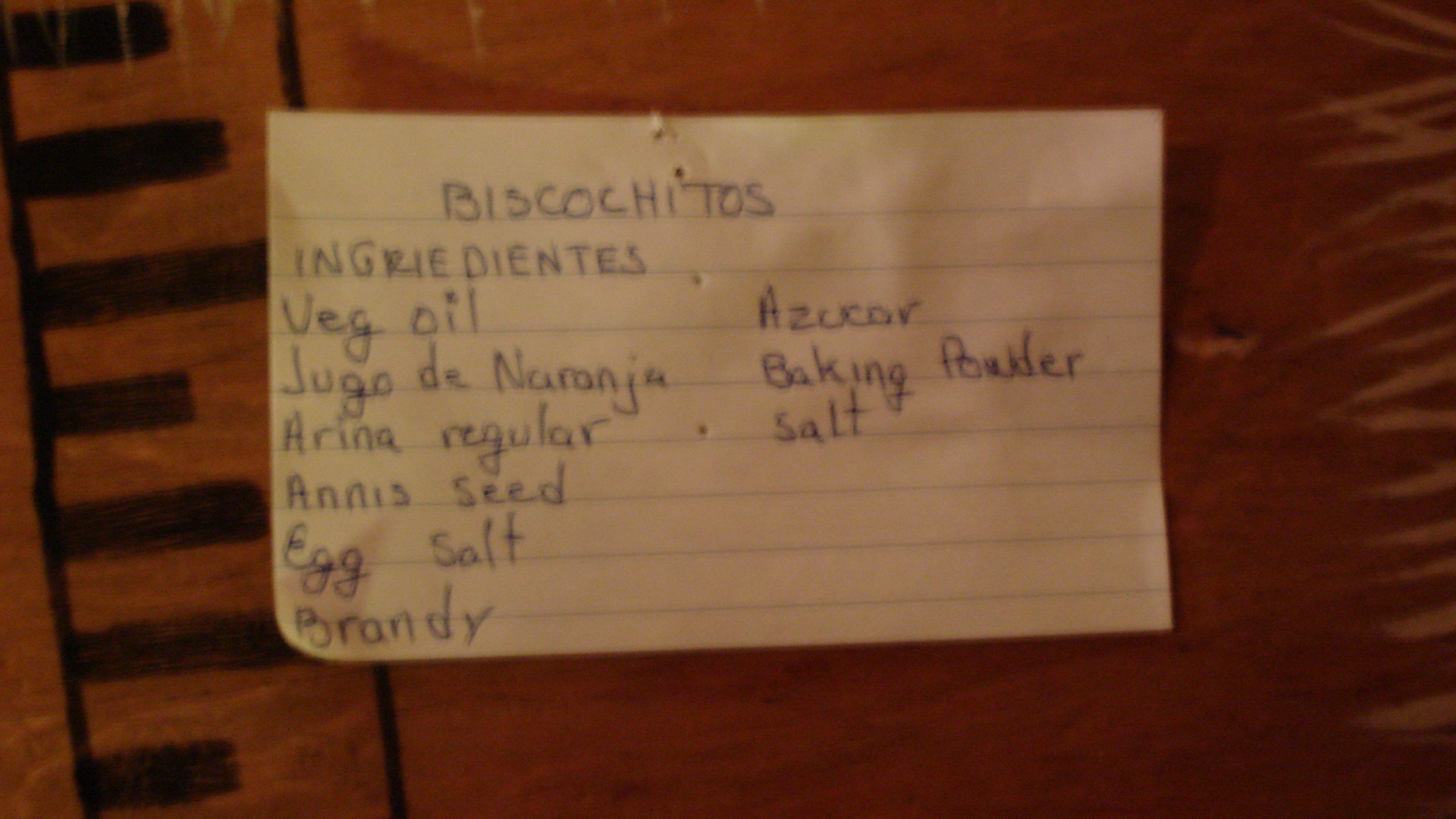

Besides the art, we also went to Santa Fe for the food. The place has about as many good restaurants as it does art galleries. Let me mention some of our favorites, and keep in mind that we were intent on satisfying our Mexican food cravings. Twice we ate at Café Pasqual’s, once for a spectacular breakfast and once for a spectacular dinner. Because we did not have reservations for dinner, we were relegated to sit at the common table, but the food was just as good and the other folks around the table had interesting stories to tell. Go there if you can and hope you can get in. Twice we ate at the restaurant at La Fonda (one of the oldest hotels in town and right off the main plaza). Here we had most wonderful, New Mexican, Mexican food, the kind I had been imprinted on in my youth. During one meal, we had some cookies that were unusual and beyond belief tasty. Beth asked how they were made, and the waiter took down the recipe from the kitchen wall and brought it to our table. Here is the photo I took of the recipe. It is mainly in Spanish and has no amounts; so we may have to experiment to come up with the same delicious cookies.

We also had great meals at The Shed (in the middle of town) and The Compound (on Canyon Road). We ate twice at an old-fashioned drugstore that has been on the corner of the main plaza for many years—the Plaza Café. It has booths, tables and a lunch counter, and it serves the best posole soup (with hominy) one can possibly find and also the best sopaipillas for dessert (a most wonderful deep fried dough, especially with honey). I have eaten at the Plaza Café on every trip to Santa Fe.

The last restaurant I want to mention was a family run Mexican restaurant outside the town of Espanola on the high road to Taos. It is called El Paragua. Wonderful food, and the old grandmother was our waitress.

Along the High Road

For one day we rented a car and drove north of Santa Fe to two pueblos and then along Route 76, the High Road to Taos. First, we visited San Ildefonso Pueblo. Protocol is that visitors to the Indian pueblos should check in at the entrance and obey any special regulations; for example, visitors are never allowed in the religious sites in the kivas. San Ildefonso is the home of the potting family of Maria Martinez and many other wonderful potters. However, on the day we visited nothing was happening, and we saw few people. We were quiet and did not pry. Here is a photo of their main kiva (from the outside of course).

We then visited Santa Clara Pueblo, also the home of many superb potters. Fortunately for us it was a feast day at Santa Clara Pueblo. Puebloan tradition is that on a religious feast day when members of the tribe come to their ancestral homes on the pueblo, even if they live in other places, they also welcome visitors. Hospitality is a must for these folks on feast days. They first have ceremonial dances, usually performed by the youth of the community, with different dances performed by different families. Then they gather in various homes for dinners, and they invite visitors into their homes to join in the dinners. When we arrived, we first found the home of Sammy Naranjo, which was open for the sale of his pottery and that of his sister. We were invited in and looked at his pottery. We also bought a small pot, done in both black and brown and with sgraffito carvings of the traditional Avanyu, the water serpent that brings water to the land. The undulating serpent represents a flash flood stream running down an arroyo (gully or wash) during the rainy season. We felt like intruders, a little out of place, because his family was getting dressed in their dance costumes for the Buffalo dances to follow. But we tried to be as respectful as possible, and they were as polite and welcoming as could be. One of his relatives came in and when he saw us invited us to his house to the dinner afterwards. We knew that it was polite to accept, but we just couldn’t go because we felt like such intruders and we knew that they did not have much and were inviting us in. I am not sure if we should have gone or not. We did stay to watch the various families do the buffalo dances. During these dances, nobody claps or speaks because the dances are considered sacred. We asked if we could take pictures, and Sammy said that we could of his family dancing. Adults played drums and chanted while the teenagers did the dance, with large buffalo headdresses on and traditional costumes. After the dances, those looking on simply drove away or went to the various homes to eat. See the photo below of the Naranjo family during their dance.

After visiting the pueblos, we drove on the High Road to the Hispanic town of Chimayo. First we stopped at the Chimayo Trading Company to look at pottery, jewelry and Navajo rugs. Here was an old fashioned type of store with an owner who knew and loved all his wares and knew personally all the artists and creators who had made them. He had a particularly spectacular room full of Navajo rugs. We talked to him for about an hour and then went on our way to visit Ortega’s Weaving Shop where Mexican style weavings were made. We then moved on to our main destination: the Santuario de Chimayo, a Catholic church built in the early 1800s. The story goes that, before there was anyone living in the area of Chimayo, a wandering priest found an old wooden cross stuck in the dirt. He took this as a sign from God and had a humble church, with dirt floors built on the site, still standing pretty much as it was originally. People made pilgrimages to the church and soon discovered that when they rubbed some dirt on their bodies, taken from the very spot where the cross had stuck in the ground (now inside the church), they were miraculously healed. Like the healing waters of Lourde’s in France, the Chimayo Santuario became famous, and pilgrims still come here for the healing powers of the dirt. Another church next door is also a sanctuary for sick children. We also gathered some dirt from the spot to take to some of Beth’s friends suffering from cancer. (Of course, as you might surmise, there is also a gift shop next door.)

Nearby we found an unusual store that specialized in three items: ristras (bunches of red chili peppers hung out to dry and often hung as decorations at Christmas time), Santos (Hispanic wood carvings of various saints, some of them quite good, and all representing Mexican folk art), and popsicles. Yes, they did indeed sell these three things. Along with the ristras they sold bags of ground chili peppers of various varieties. You see, central New Mexico is known for growing some of the best chili peppers in the world, maybe one reason their Mexican food is so tasty.

After leaving Chimayo, we drove on up the High Road to another Hispanic farming town, Truchas, actually just a gathering of houses, a funky general store, an old church, and a few art galleries, at 8000 feet, along the narrow road along a ridge winding up through the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. Remember, this was early January, and we were in the neighborhood of winter.

Alas, we ran out of time, and had to turn around and return to Santa Fe. And, alas, we ran out of our vacation as well and had to return home. On our way back to the airport, sharing a taxi with another person, we learned that she was a wealthy woman from New York who had a second home in Santa Fe and came out often for the art community. From her conversation with the driver, we gathered that there were clashes between the old timers, the poorer people who were still fighting for decent schools and often left out of the wealth of the Santa Fe art and fashion scene, and the artsy-fartsy types who come in and try to take over the town. I love Santa Fe, but it is not paradise. I hope it retains its charm; its beauty, art and creativity; and its funky, friendly people. And I would wish good schools and wealth for all its citizens.