Our Trip to Berlin

Our Trip to Berlin Mick Watson 2017

Over the years I have on occasion sung a song that was made popular back when I lived in Berlin (from June, 1963 to December, 1965). Lately, I find myself singing it again:

Ich hab so Heimweh nach dem Kurfürstendamm. Ich hab so Sehnsucht nach meinem Berlin. Und seh ich auch in Frankfurt, München, Hamburg, oder Wien Die Leute sich bemühn, aber Berlin bleibt noch Berlin.

Ich hab so Heimweh nach dem Kurfürstendamm. Berliner Tempo, Betrieb, und Tamtam. Hab ich auch keine Wohnung, und schlaf ich Nachts auf Heu, Ich bleib Berlin, meiner alten Liebe treu.

Here is my translation:

I am so homesick for the Kurfürstendamm (the major shopping street in what was West Berlin). I have such a yearning for my Berlin. I also see in Frankfurt, Munich, Hamburg, or Vienna The people really try hard, but Berlin still stays Berlin.

I am so homesick for the Kurfürstendamm. Berliner tempo, activity, and vibe. If I didn’t have a place to live and slept at night on hay, To Berlin, my old love, I’d still stay true.

On June 26, 1963, I flew from Frankfurt to Berlin, landing at Tempelhof Airport, the same airport made famous by the Berlin airlift of 1948-49 when the Soviets cut off all roads and railroads into West Berlin in an attempt to force the city to come under the control of the Soviet Union, and in response western countries, led by the U.S., flew flights around the clock into Tempelhof, bringing in the supplies needed to keep alive this city under siege. Also on my flight to Berlin on that June day in 1963 was Willy Brandt, the famous mayor of West Berlin, who worked so hard to keep the city afloat despite all the trials and tensions. He was returning to be by President John F. Kennedy’s side for his now famous Berlin speech. Later that day, despite being sleep deprived, I listened on the radio to Kennedy’s speech. Little did we know that the speech would become so memorable.

I was in Berlin to serve a voluntary, unpaid mission for my Church, to teach and preach, and to provide service to others in various ways (e.g., we taught English classes, we poured cement at building projects, we organized a youth sports program to mix in games of soccer with American basketball).

I think it would be helpful to review some of the history of Berlin in those tense times. At the close of World War II, as the Allied Forces were closing in on Hitler and the Nazi headquarters, located in Berlin, the U.S. forces were closest and probably could have reached the city first, but under some political arrangement, which I can’t quite fathom, they pulled back and allowed the Russians to enter the city first and take control of the city center. Many Berliners told me that they were starving at the time in their partially bombed-out city and were hoping that the Americans would beat the Russians into Berlin. They hoped for relief from the Americans, but they feared what the Russians would do. In large part because of the devastation the German Army had rained down on Russia, the Russians were motivated to get revenge. They were indeed to be feared at that time, and they lived up to the fears as they dealt with the Berliners with a vengeance. I heard of one instance in which the Russian troops learned that one of the most expensive and highly gilded hotels in the world—the Hotel Adlon—on the famous Unter den Linden Boulevard, next to the Brandenburger Tor (Brandenburg Gate), also had the best wine cellar in the world. Russian troops made their quarters throughout the hotel, often tearing things apart and washing their potatoes in the toilets (they didn’t know what else the contraption could be used for), and eventually found the famed wine cellar. They got rip-roaring drunk and by accident burned down the hotel. (It has since been rebuilt.)

After American troops entered the city, some semblance of order was restored, and after the four major allied powers—U.S., Great Britain, Soviet Union, and France—had met in nearby Potsdam and worked out a plan for post-war Germany, they divided the country into four sections, one to be governed by each of the four countries. Berlin, smack dab in the middle of East Germany—the Soviet’s sector, was also divided into four sections. And then the post-war trouble started. Russia hated having Berlin so divided. After all, it was located in their sector, and they wanted it all. Several times they tried to block the western countries from entering their section. (For example, in 1958, Nikita Khrushchev issued an ultimatum for all western powers to withdraw from Berlin. And East German authorities made it more difficult for West Germans and East Germans to visit across the borders.) By 1961, when Kennedy was President (he was president only a short 2 ¾ years, from January, 1961 until November, 1963, when he was assassinated), 4 ½ million East Germans (about 20 % of their population) had escaped East Germany for West Germany, traveling mainly from East Berlin into West Berlin. And this hemorrhaging of the population was also a brain drain for the East. The professionals, the scientists, the skilled workers, were mainly those who were leaving.

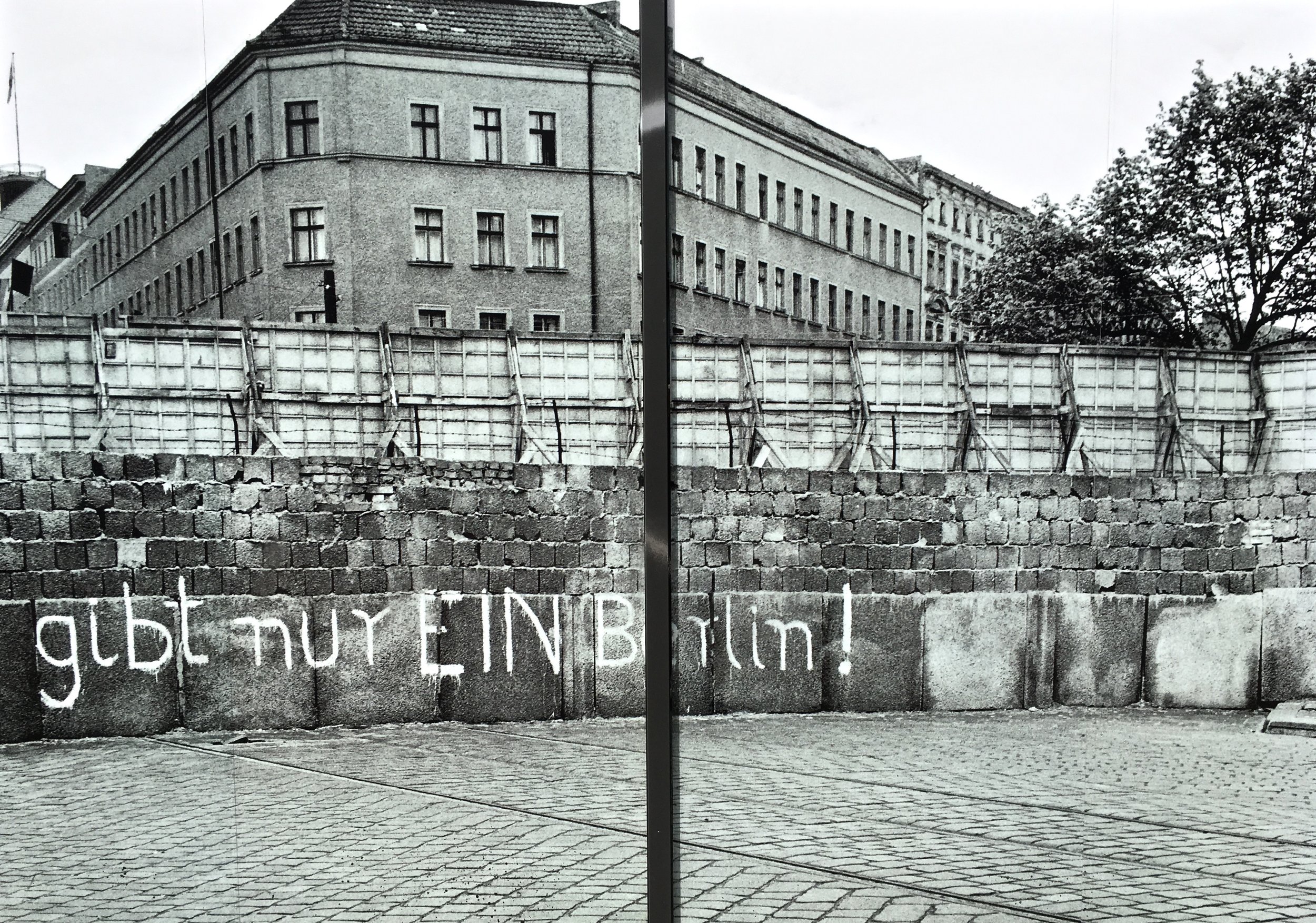

As you can imagine, tensions continued to rise. There was a saying: “No matter which direction you leave from Berlin, you end up going East.” Now panicky East Germans tried even harder to leave from East to West Berlin. Kennedy added about 200,000 more American troops to the area. And then, as everyone knows, the Soviet Union and East Germany, in August, 1961, erected a barbed-wire fence around Island West Berlin and constructed Die Berliner Mauer, or as Mayor Willy Brandt called it, Die Schandmauer, the “Wall of Shame,” along the border of the East German sector. Almost overnight it seemed to appear. It cut off streets, subways, streetcar lines, and buildings. A barren no-man’s land was constructed on the East Berlin side, and guards were stationed along the Wall in guardhouses with instructions to shoot to kill anyone who tried to cross the Wall. Of course, West Berliners were not rushing to cross into the East, but the other way around, and over the course of the Wall’s existence, especially in those first years, hundreds of people were killed, quite a few while I lived there. (At one time I lived about a tenth of a mile from the Wall, which crossed over and blocked off the street I lived on.) West Berliners hated having their city divided, their country divided. On the western side, graffiti messages constantly appeared on the Wall, such as the one that said, “Gibt nur ein Berlin.” (There is only one Berlin.)

In October, 1961, two months after the Wall had been erected, the Soviets and East Germans tried to stop all allied personnel from crossing into East Berlin (as was the allies right under the former agreement). To enforce this decree, Krushchev ordered in tanks to block the main crossing in the American sector. Kennedy, in turn, authorized tanks to be sent to the area, and both sides ended up having more tanks than one could imagine facing each other, armed and loaded, on Friedrich Straße at Checkpoint Charlie. Eventually, each side backed down, but at this point, the Cold War almost became a hot war, and Berlin became truly the epicenter of the Cold War. So, you see, the Cuban Missile Crisis was not the first serious confrontation that Kennedy had with Krushchev.

Under these conditions, on June 26, 1963, the day that John F. Kennedy and Willy Brandt and I came to Berlin, Kennedy gave the speech that endeared him forever to West Berliners. They loved him more than they loved their own political leaders. The loved him more than Americans loved him. When he was assassinated in November of that same year, they mourned with a pain that tore them to their very souls. (I was there, I know, I saw it.)

I have since re-read Kennedy’s talk and listened to it again. It was Kennedy at his best—he seemed to pour his heart and soul into that speech. Here is how he ended it:

You live in a defended island of freedom, but your life is part of the main. So let me ask you…to lift your eyes beyond the danger of today, to the hopes of tomorrow, beyond the freedom merely of this city of Berlin, or your country of Germany, to the advance of freedom everywhere, beyond the wall to the day of peace with justice, beyond yourselves and ourselves to all mankind….All free men, wherever they may live, are citizens of Berlin. And, therefore, as a free man, I take pride in the words—“Ich bin ein Berliner.”

Some made fun of Kennedy’s statement, but they were Americans and others, not Berliners. Berliners didn’t make fun of him. They knew what he said and what he meant. You see, in German, it is typical to leave off the article when one says who one is or where one is from. A person would say, “I am Berliner” or “I am American.” Kennedy said, “I am a Berliner,” which could mean, “I am a jelly-filled donut,” because “Berliner” was the name of such a pastry, just as Frankfurter is the name of a sausage. But using the article is still correct German. So, let it go, Americans.

In 1989, when the Soviet Union collapsed, the Wall was torn down, and, in 1991, Germany was officially reunited.

On May 26, 2017, exactly one month shy of 54 years after my first flight into Berlin, for the first time I returned. I took a train from Frankfurt to Berlin. I learned that Tempelhof Airport had been made into a memorial park, which is currently housing refugees who have fled from the Middle East. I met my youngest son, Ethan, in the huge, futuristic, otherworldly Haupt Bahnhof (main train station) and we stayed in a hotel nearby. Ethan had just completed a semester abroad studying German, first in Freiburg and then in Berlin. He loved the experience and managed to travel on his own and with others to several places in Germany, France, Switzerland, Italy, and Austria before ending up in Berlin. We both are struggling to speak and understand German, and with all that I have forgotten, I did indeed need the practice. But we did attempt to communicate almost entirely in German with others.

Luckily I had Ethan as my guide because I no longer could find my way around the city. It has changed and grown so much. But it is still a vibrant, edgy, high-energy city, full of life, art, culture, and activities, like no place else in Europe that I know of. The transportation system is phenomenal—U-Bahns (subways), S-Bahns (elevateds), Straßenbahns (streetcars), and busses, all intersecting, and all running on time (so typically German). So we got around easily.

Shortly after my arrival, we visited the beautiful home at Am Hirschsprung Straße 60 in Dahlem, the place I first stayed when I listened to Kennedy’s speech. Did I visit the memorials to the Wall and to Checkpoint Charlie on Friedrich Straße? Of course I did. We also visited Mauer Park, where the Wall had cut through the park, now a memorial and a large flea market. (Just as the red brick Freedom Trail in Boston guides visitors to important historical sites, in Berlin a stone and red brick trail traces the path where the Wall had stood.) We visited Schwedter Straße, where in 1989 people first broke through the Wall and, in droves, stormed from East Berlin into West Berlin.

One late night, as our S-Bahn stopped at a lonely station, a tense quiet seemed to pervade the place. Ethan told me that Berliners told him that they still feel the spirit of the border and sense when they are crossing from West into East, such as at this station, even though there are now no markers of the two sectors. East Berlin, which in 1963 was depressed and consisted mainly of a drab, gray color, now sports lively neighborhoods and sections of wonderful restaurants, clubs, beer gardens, and art museums. (Prenzlauerberg, where Ethan had been living, was one of those vibrant neighborhoods.) However, the ghost of East Berlin may still be lurking about. Ethan also said that some former East Berliners have an unexplainable nostalgia for the former East Berlin.

Back in the day, in 1964 I believe, I was asked by the president of our mission if I would like to make some forays into East Berlin through Checkpoint Charlie and smuggle clothes, medicine, and some written material to people we had contact with in the East. I said sure. I realize now that this action was foolhardy and a dangerous and stupid call on the part of our mission president (so much to lose for so little to gain), but I was young and stupid and up for such an adventure. As Americans, we could cross over, but the guards checked all our luggage carefully. We would fill up a suitcase, leave about half the belongings with people in the East, and always have enough in the suitcase on our return to arouse no suspicions when the guards again checked. On one occasion I was invited to go with a small group of Americans to Leipzig ostensibly to attend the Leipzig Trades Fair, an event that East Germany organized to show off their many products and progress and to make some money selling to the visitors (every visitor to the Fair was required each day while there to spend some hefty sum). But our actual purpose in visiting was to attend a religious conference that brought in people from several Eastern block countries, many who had not been able to attend any religious services in years. We knew that we had secret police attending our meetings; so everyone was careful to say nothing political or subversive. And on this occasion we smuggled in a lot of clothes and medicine and smuggled out papers of genealogy and histories and records, pressed flat against our chests under our clothes. I thought it was so much fun until we got to the border with West Berlin and for some reason the guards suspected something amiss. They took us into a separate room and prepared to do strip searches. You can imagine how my heart was now racing. I was not really cut out to be a smuggler. About the time they started the search, alarms went off at the checkpoint, and lights lit up the nighttime sky. The guards had discovered that in several meat trucks transporting beef and hog carcasses into West Berlin, young children had been drugged and sewn into the carcasses to try to smuggle them into the West. The guards hurriedly dismissed us because they had found a bigger catch. We made it through because these poor children and their drivers were caught. On that night, I learned that the entire East-West enterprise was not fun. It could end in tragedy.

Back in 1963-65, as I got to know many Berliners and could call them my good friends, I found that they brought up three themes again and again, themes that seemed to weigh heavily on their minds. First, as I have mentioned, was the trauma of the War and the entry of the Russians into their city. Second, as you might imagine, was talk of their hatred of the Wall and its effect on their city. And, third, was what seemed like a universal feeling of guilt for what the Nazis had done and for the Holocaust. Most tried to explain how they had had no idea that these atrocities were occurring and how they had been powerless to do anything about it. Who knows? I never openly questioned their complicity in the Holocaust. Rather, so many of them brought it up on their own and seemed to be compelled to talk it through, especially with an American. I don’t know if those themes are still compulsively discussed today.

On this recent visit, throughout Berlin, and later in Leipzig (more about Leipzig later), as Ethan and I walked through various neighborhoods, we encountered Stolpersteine (Stumbling Stones)—small brass squares embedded in the cobblestoned sidewalks. On each one was engraved a person’s name, when the person was born, when he or she was arrested, and when and where the person was killed. These memorials have been placed in the sidewalk in front of the last residence of each person (mostly Jews) whom the Nazis deported and killed in the Holocaust. The idea is that a person, while walking along and not necessarily thinking about it, might stumble onto these markers and be forced to think about what happened and remember the memory of that person. These Stumbling Stones are now located throughout Germany and I believe in several other countries as well. I found them to be sad and moving memorials to these tragic deaths.

And while I am on the subject, in Leipzig we encountered another, unusually sad and moving Holocaust memorial. We unexpectedly came upon, almost stumbled upon, a small triangular park, green and nicely maintained. In the middle of the park, on a raised stone platform, are 140 brass chairs, arranged in 14 rows of ten each. We learned that in 1938, the Fascists burned down the main Jewish synagogue that stood on this site and then arrested 14000 Jews who prayed at this synagogue. All of them were killed. There are no entrances into the park, no walkways. You see, nobody is ever supposed to sit on those 140 chairs again; they represent the 14000 who lost their lives. It made me think like other memorials have not done, and even as I write this, it brings tears to my eyes. As Kennedy noted, each of our lives is part of the main.

So, what, you might ask, is there about Berlin that makes it so vibrant and delightful? After all, what I have written so far doesn’t seem to exhibit delightfulness. Well, on this recent visit, Ethan and I did view the magnificent Brandenburg Gate, and unlike in 1963 when it was blocked off by the Wall, we could now walk under it. We visited Potsdamer Platz, so influenced after the war by modern American architecture. I was happy to see all the Litfaßsäulen, just like they were back in 1963. These are those squat columns on the streets that are used to post ads and announcements of various events. I suppose they are found throughout Europe, but for me they represent Berlin.

One aspect I encountered was not present in 1963. In many sections, we saw large, pink pipes running from the ground and following streets. Ethan informed me that a good share of Berlin had been built on a swamp, and the water level has been rising. These pipes are supposedly temporary in a massive effort to drain the swamp.

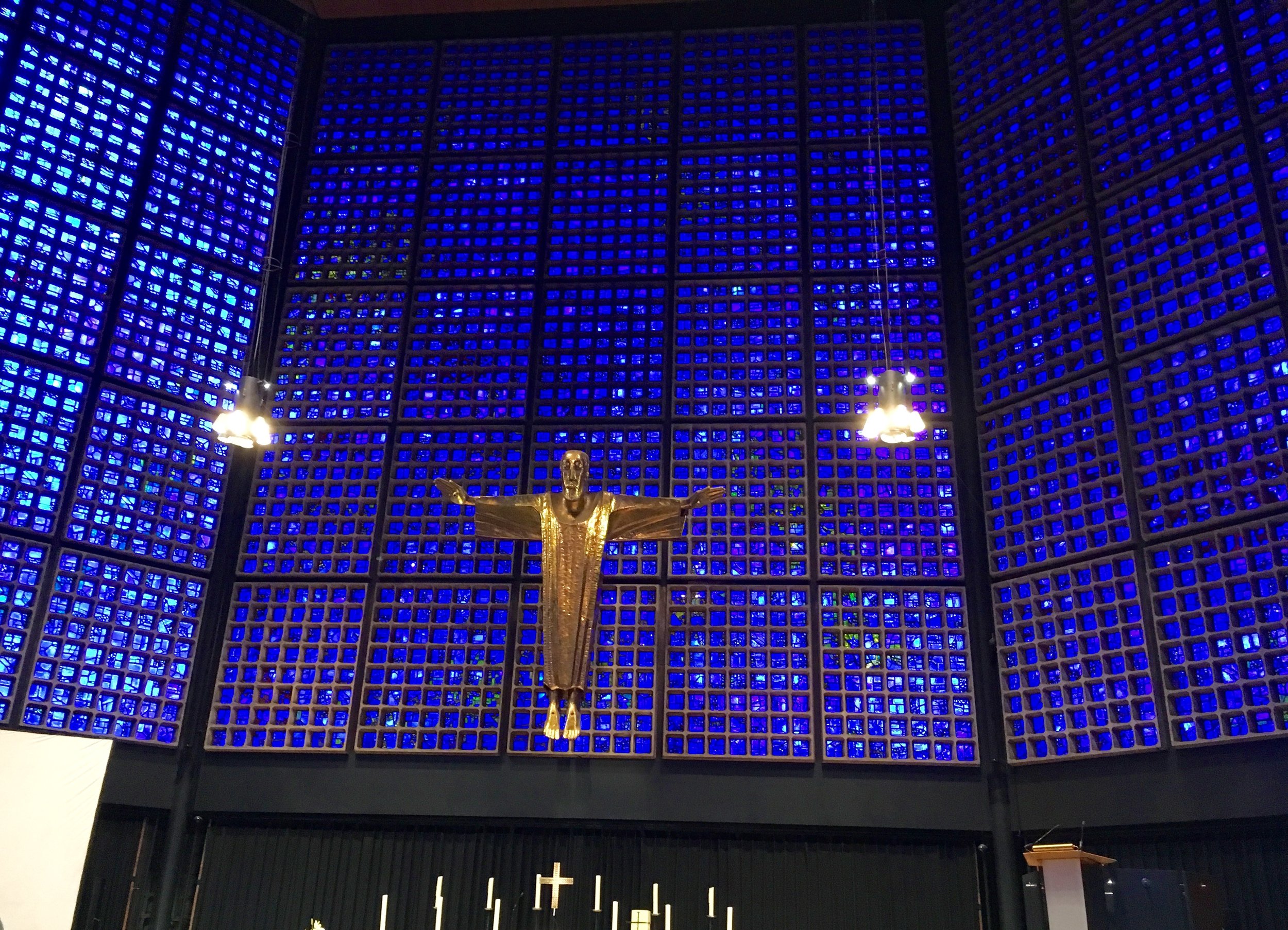

And of course we visited the Kurfürstendamm, still a main boulevard in Berlin. At the beginning of this boulevard stands the Gedächtnis Kirche (The Kaiser Wilhem Memorial Church). It was there in 1963—the remains of a bombed out church that has been left standing as a memorial, with a modern church and steeple built around the old remains. Inside the old part is a damaged statue of Jesus; inside the new church, surrounded entirely by blue stained glass is a modern, gold Jesus. The memorial looked the same as I remembered it from 1963.

While we were on the Kurfürstendamm, we ran smack dab into the middle of a huge group of soccer fans from Dortmund, all decked out in their yellow jerseys and drinking Berliner Kindl beer. In talking to them we learned that the Dortmund team was playing the Frankfurt team that night for the national championship. To avoid confrontations, the city had wisely separated the fans of the two teams into completely different sections of the city; so we only got to hear about the superiority of the Dortmund team.

Unlike in 1963, when I could not get a hamburger or pizza, now Berlin is a city hosting an international cuisine. We tried to eat well, and although we succumbed to pizza, spaghetti, Argeninian food, and Turkish Döner and Schawarma, oh so good, at Gemüse Kebop, we tried mainly to get our fill of traditional German food. We drank two of my favorite drinks: schwartzer Johannisbeersaft (Black current juice) and my beloved Faßbrause (sparkling apple cider, but with something in it that makes it so much better). Of course, all around us, the drink of choice was beer (this was Germany after all). We ate Currywürst at sidewalk stands, and great food in the phenomenal food court at KaDeWe (Kaufhaus des Westens), a huge, old, and elegant department store that has been in Berlin forever (or so it seems). The food court is bigger and more astounding than the one at Harrods in London. Two of my favorite German meals were, first, Rinderroulade (beef roll stuffed with spices) with Spätzel and Rotkohl (cooked red cabbage sauerkraut) at a great little restaurant called Joseph Roth’s Diele. Ethan had Wienerschnitzel. The second was Kohlroulade (cabbage roll stuffed with meat) at an enclosed courtyard restaurant called Sophiastraße 11, near Alexander Platz and Hackescher Markt. For breakfasts, we gobbled down a good deal of German bread and a variety of cheeses and Würst. Perhaps the best meal of our trip was later in Leipzig at the old Ratskeller (a traditional restaurant in the cellar of the town hall), where I again had Rinderroulade and Ethan again had Wienerschnitzel.

So, you may ask, is that all you did was eat? What about the art and culture? In Berlin we attended an organ concert at the Berliner Philharmonie, that now old concert hall that still looks incredibly modern and has such amazing acoustics. This was a strange concert consisting of a transcription of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring for solo organ. I liked it, though I prefer the piece performed with full orchestra. (In 1965 I saw the Berlin Ballet perform a memorable Rite of Spring.)

Ethan and I had wanted to hear a performance of the Berlin Philharmonic in the Philharmonie, but that didn’t work out. It did make me remember four phenomenal concerts I had heard in that famed concert hall back in 1964-65: first, the Berlin Philharmonic, directed by the legendary Herbert von Karajan, playing Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony; second, Andrés Segovia playing solo guitar; third, a Miles Davis concert; and fourth, Ben Webster playing sax. In our home we have a quilt that was based on a photo of the bass section from a video of the Berliner Philharmonic, conducted by von Karajan, playing Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony. It always reminds me of that phenomenal performance, with von Karajan, dressed in a black tunic, his white hair flying, who closed his eyes for the entire concert and conducted without a score. Though diminutive, he was a commanding presence.

Perhaps a stretch to include it in a description of Culture, but Ethan and I listened for some time to a street band in an outdoor food court that likely provided the worst music I have heard since attending my kids’ elementary school band concerts. A group of guys had come in from Leipzig to celebrate a bachelor party for their lead singer. Most of them played brass instruments (a number of trumpets, trombones, a tuba), and those who could not play were assigned to various percussion instruments. One guy played a red, plastic recorder flute he probably picked up in grade school. The singer was even more out of tune than the band, but they played it straight, as if they actually had some talent. The best part was watching people walk by, listen for a moment, and then wince in pain. Some moved quickly away, but a few of the sensitive members of the audience, such as ourselves, lingered on to laugh and cry at the same time. I know their music brought tears to my eyes. To cleanse ourselves, we later heard jazz at the B Flat Jazz Club.

Ethan and I also visited two art museums, the Alte Nationalgalerie on Museum Island in Berlin, and the Museum der Bildenden Künste in Leipzig. The Berlin museum focused on 19th Century paintings, and though there were many Impressionist paintings to be viewed, the bulk of their collection was of earlier German art, from Classicism to Romanticism. It was a pleasure seeing so many paintings that I was not familiar with and some that I have not seen outside of Germany (e.g., the Romantic and often humorous and tongue-in-cheek paintings of Carl Spitzweg and Wilhelm Busch). The Leipzig museum covered a range of art, but again I was impressed by the number of paintings from German artists, who were unknown to me and in juxtaposition of Romantic with modern art. In both museums I especially liked seeing a slew of Romanticist paintings of families, children (often in school classes), and subject matter that today would probably be considered kitschy, but were certainly not taken that way when they were painted. And there was an abundance of humor shown in those paintings (e.g., school children in class misbehaving while a frustrated teacher is about ready to throw in the towel, a dog being made to wait painfully for a treat of sausages, a man holding an umbrella over his bed to keep out the rain from a leaky roof while he composes poetry.) And then there were two paintings in stark contrast to each other. One was a haunting painting of a partially visible nude woman sinking into blue black darkness and seeming to beckon the viewer to follow, entitled “Sin.” The other was a picture by Fritz von Uhde of Jesus visiting some families in a humble German farm house, entitled “Lasset die Kindlein zu mir kommen” (Let the little children come unto me). And we found one painting from an East Berlin artist of an East Berlin apartment house (which had rigid rules about residents keeping everything on the balconies the same as everyone else). In the painting one could see subtle attempts to express some individuality in some of the units.

Besides all this high art, we found some memorable street art as well. We saw ubiquitous Berliner Kindl signs just like back in 1963. We saw two unusual pieces of graffiti—one a beautiful picture of a girl on a tire swing and one a picture of Max and Moritz, beloved cartoon characters from stories drawn and written by Wilhelm Busch. In Leipzig we saw a bicycle on the sidewalk that I can only take to be Salvador Dali’s personal bike. And Ethan pointed out what we took as a funny sign on all the U-Bahn and S-Bahn cars. It showed a stylized graphic indicating that on the train, one could not bring on food or drink or drink alcohol or smoke, but one could bring on his or her horse. Ok, it was a dog one could bring on, but it sure looked like a horse to us.

As we walked around different neighborhoods in Berlin, I was reminded once again that some things do indeed get lost in translation, and one must be careful with words that do not mean the same thing in two different languages. As a supreme example, we came upon one street called Dickhardt Straße. (How would you like that street to be your address?) The origin of that street name bewilders me; it should mean “thick, hard or tough street,” but the street was a charming, curved residential street. Maybe it was named after someone who first lived there and was a thick, tough guy.

In that same neighborhood, we came upon an area where a school had just let out. As some exuberant girls ran by us, one of them bumped into me and then ran on down the block. I didn’t think anything of it, but I saw her stop a few houses away, look down at the ground, and then turn around and walk back to me and say, “I’m sorry I bumped into you. I didn’t mean to do that.” I also thought about how a kid got up from a seat on the U-Bahn and offered it to me. I hate to think that I am somebody who looks old enough to need a seat, but it was a kind gesture. Ethan and I talked about these incidences and decided that no matter how considerate and kind you think you are, German kids are Kinder.

And so on our last night in Berlin, we once again returned to the Brandenburg Gate for a beautiful moonlit view. The next morning, we took the train to Leipzig. Leipzig is nothing if it isn’t Johann Sebastian Bach’s town. He did indeed live there, perform there, and compose there for many years, and now one is reminded at every turn of that fact. Indeed, cafes and stores are named for him. The Thomas Kirche where he played and performed looked much the same as it did in 1964 on my first visit. We were hoping to hear a Bach organ recital in his church, but no music was to be heard on the days we were there. We also visited another old church—the baroque St. Nicholai Kirche, with its grand marble friezes, its unusual lavender and green palm columns, and yet another impressive pipe organ.

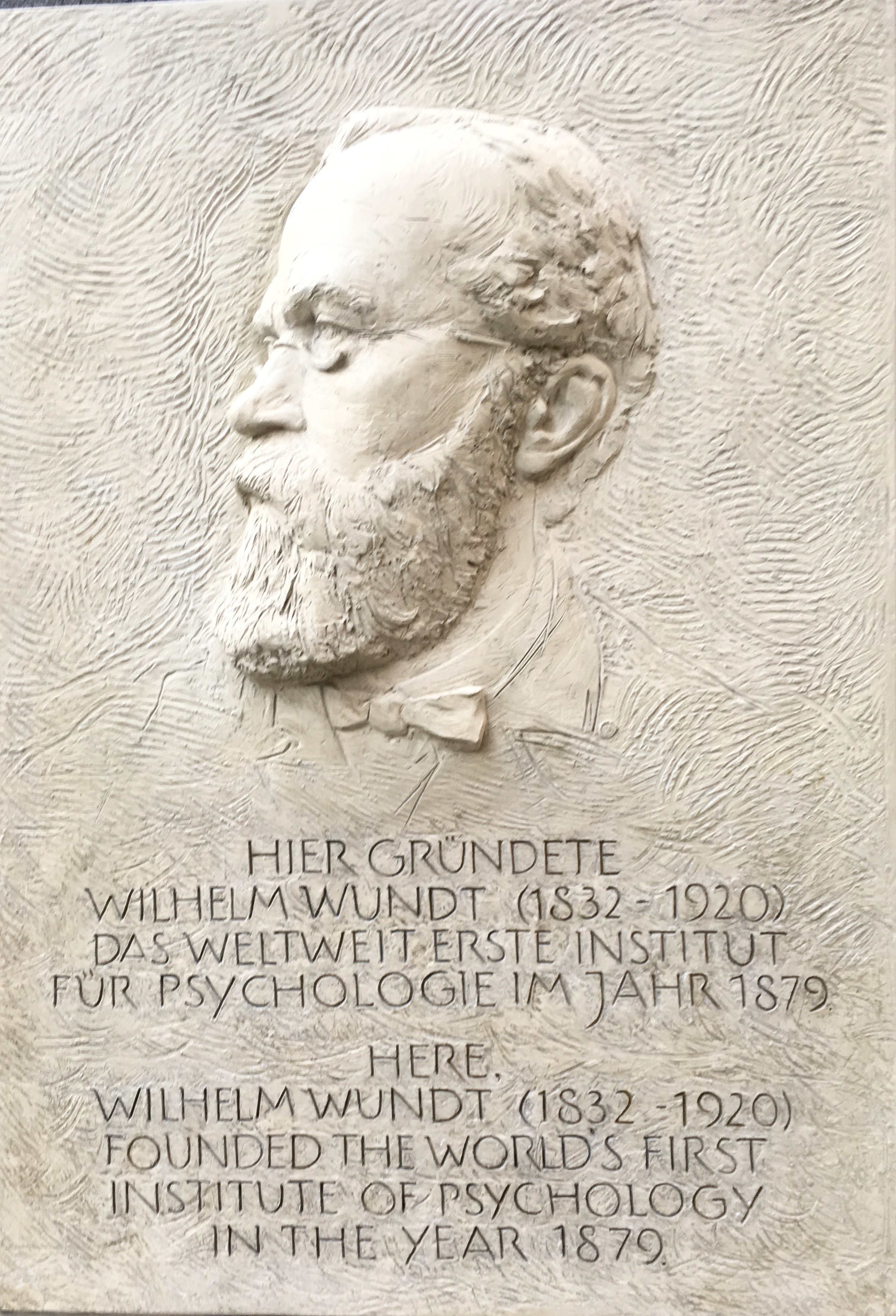

We also walked around Leipzig University, an old, old university but sporting a modern, futuristic campus, smack dab in the middle of the city. The buildings, one the tallest in Leipzig, were most beautiful with blue and green stained glass and sparkling steel. To my delight we found in one corner of the campus a marble plaque honoring Wilhelm Wundt at the place where in 1879 he founded the first psychology institute and lab in the world. He was the father of modern experimental psychology. We discovered that Leipzig has many alleyways cutting through the buildings and running between the main streets. Interesting shops and cafes are often located in these inner courtyards and alleys. On our last day it was raining and we missed seeing the Leipzig Zoo, supposedly one of the best.

After our visit to Leipzig, we took the train to Frankfurt to discover first hand that Frankfurt is the business and financial capitol of Germany. It sported an interesting mix of modern, fast-paced, business high rises next to slower-paced, old areas that still looked like old Germany. I liked the combination. Though we didn’t attend the opera, we visited the old opera house. Apparently, they were holding a fancy party there. On the balcony were men and women dressed in formal wear eating and drinking and carrying on. As we watched, several men in trim dark suits walked directly out of Gentlemen’s Quarterly and to the Opera House. They were no doubt carrying secret weapons and were on an espionage mission. We ended our trip by visiting typical tourist shops filled with Cuckoo Clocks from the Schwartzenwald, Nutcrackers, Bierkrüge (Steins), and music boxes. Ethan bought beer steins as gifts, and he once again tried on the Lederhosen that he had purchased previously in München (Munich). Now where is he going to wear them? I asked him if, when he wore them in München, the Germans laughed at him.

Before getting on our flight home, as a sad farewell, I ate a Berliner in honor of Berlin, though I purchased it at the Frankfurt Airport. Already, in writing this travelogue, hab ich so Sehnsucht nach meinem Berlin.