Our Trip to Norway

Our Trip to Norway

July, 2017

If I never see another statue or figurine of a troll, it will be fine with me. Vikings are another matter. After all, Vikings are in my blood, climbing around in my family tree. So let me begin with my favorite Viking—my mother, Thora Bergeson, named after Thor, that fierce god of thunder, storms, and fighting, swinging away with his awesome, magic hammer, son of Odin, probably the main Norse god in the Kingdom of Asgard. But my mother was not fierce and taken to fighting. Maybe that’s why her Scandinavian grandmother always called her “Little Tora,” using the Old Norse pronunciation of her name. Actually, it just occurred to me that we have another little Viking in our family. Our youngest granddaughter has two Viking names: Britta Thora Watson. And, indeed, I believe that she is a Viking of sorts. (Someone we met in Oslo during Beth’s and my two-week visit to Norway this July told us that the name Thora is making a comeback.)

So what is it with these Vikings—both the ancient and the present-day types? Here is a brief history. Way back when, Germanic tribes populated most of northern Europe, and some of those tribes became the original Vikings. Around year 790, give or take a hundred years or so, the Viking era began. These folks who lived up in the north way, where most other tribes were reluctant to go, probably out of necessity developed a culture of working together and helping each other to survive. Inheritance went from father to the eldest son. The other sons got squat; so this may have motivated many of them to take to long voyages to fend for themselves. In any case, they became superb ship builders and navigators. Their wooden long boats (of which we saw the oldest two in existence, well preserved in the Viking Museum in Oslo) were marvels of stability and speed for those long voyages, but, wow, those sea voyagers must have been tough, sailing in all those stormy waters with little or no cover. Besides being ship builders and sailors supreme, the other attribute that these folks developed was being brave, fierce, and downright nasty warriors. Those that lived in the area that became present-day Norway sailed west and raided and killed (but also traded with) people they met on many islands in the North Atlantic and the British Isles. They discovered uninhabited Iceland and then later populated it. They also populated (if you can call it that) Greenland, and, under Leif Erikson (son of Erik the Red), were the first Europeans to settle in North America (in Newfoundland), though they gave up on that settlement after a few years. Those were amazingly long voyages to be made in their open boats. Rather than sailing west, the sailors from what are present-day Sweden and Denmark went south and east, settling, trading, and raiding all through the Mediterranean and Northern Africa and even into Eastern Europe and Asia. At first, just the sailor-warriors were called Vikings, but soon the name stuck for all the Nordic peoples. They also brought back slaves and wives from these various lands and left people to settle in various locations. For example, they were the first founders of Dublin. So, you see, Vikings became a part of several cultures and left their DNA in many lands, and the Vikings themselves became a mixed group—not so pure but rather mutts like the rest of us.

While many of the men were away sailing and plundering and trading and getting more wives, the women left at home were in charge of the farms. They developed a culture that included women in some of their councils—certainly ahead of their time.

One factoid we learned was that no Viking ever wore a helmet with horns sticking out of the sides—no pictures or artifact of that type has ever been found. Helmets with horns may have been the favored headgear for Wagner in his operas, but they didn’t come from the Vikings.

So what ended the Viking era? It seemed to end in large part when the majority of the people were converted to Christianity. The story goes that in the year 986 King Olaf I of what is now Norway, on one of his voyages to some islands, heard of a Christian seer with special powers. He had one of his servants climb the hills to meet the seer and tell him that he was King Olaf. The seer told the servant, “Tell your king not to send an imposter but to come himself to meet me if he wants to hear my wisdom.” How did he know? The story gets better. So King Olaf himself climbed up to meet the seer. The seer told him that when he returned to his ships and crew he would find that they had mutinied and that the King himself would receive mortal wounds. However, the seer recommended that the king lay low for a while and he would be miraculously healed. When this actually happened, King Olaf was converted to Christianity and was baptized and determined to take Christianity back to his homeland, which he did. Of course, still possessing Viking habits, his method of conversion was to force people to become Christians or be killed. Most of his people decided to convert—what a surprise. Even though the old Viking religion rebounded, eventually Christianity spread, took over the north way and helped do away with the Viking era and all the marauding. Early Christian churches were built entirely of wood without nails. They were rather crude but included carvings inside and out (some suspiciously similar to the old Norse gods and religion). We visited one of these old Stave Churches.

We also visited some old, traditional sod houses. Birch bark was placed over the roof because it provided a good waterproof barrier. Then thick sod was laid on top of the birch bark. The sod provided great insulation, keeping the house cool in the summer but insulating it in the winter. The problem was that the birch bark was highly flammable, especially from the open fires inside the homes. (You see some relatively new homes even today that still use sod roofs, though I’m sure with some modern waterproof barrier other than birch bark.)

After the Viking era, people were still around of course. So how did they become the Scandinavians of today—the modern Vikings? The borders of the various kingdoms seemed to shift many times over the years. For hundreds of years, Denmark was the dominant country, owning Norway and Iceland as well. However, in a treaty with Sweden, Denmark ceded Norway to Sweden, and Sweden also controlled what is now Finland. It wasn’t until 1905 that Norway became its own independent country, and it was considered the poor relative to the other two. (Today, when people talk about the Nordic countries, they include five and usually call them all Scandinavian: Sweden, Denmark, Norway—the original Vikings, but also Finland and Iceland.) The languages of Sweden, Denmark, and Norway are so similar that most of these people can understand each other even when one person speaks one language and another person speaks another language.

Norway remained sparsely populated and poor with little farmland but rather a lot of forests, mountains, rocks, snow, and ice. But they also were surrounded by fjords, lakes, rivers, and oceans teeming with fish, especially cod and salmon that came down from the arctic to spawn. Unlike their earlier ancestors, they became a generally peace loving and egalitarian people. Their kings and queens did not tend to be tyrants. For example, at one time, they had nobody to be king, so they asked a German, Karl Johann, if he would step in. He said he would but only if they held a referendum and the people voted to have him, which they did. He spoke mainly French and never was able to learn to speak Norwegian, but he was so good to the people that they all loved him. (The main shopping street in Oslo, which we strolled from the central train station at one end to the king’s palace at the other, is named in honor of him—Karl Johann Gate.)

The Norwegians tended to spread themselves out in their big country, which is still the practice today, encouraged by financial help from the government so that they don’t all flock into Oslo. They only have a little over 5 million people in the entire country, and they have a tendency to keep to themselves (and as a country to keep to themselves). As we traveled up the coast of Norway and into fjords, we saw many homes and cabins isolated along the shore or up on the sides of the mountains, difficult to reach. Apparently, these were once isolated, subsistence farms or the homes of fishermen, but today many of them are the summer vacation homes of Norwegians trying to isolate themselves from others.

In April, 1940, Nazi Germany invaded Norway and occupied it until 1945. The Norwegians were surprised and not prepared for the German invasion. Most of them had thought that by remaining a neutral country the Nazis would have no need to invade and occupy their homeland. They were so wrong. Because the Gulf Stream runs up the coast of Norway and into the waters to the north, it keeps the waterways free of ice all year round, which has always been a boon to the fishing industry. But for the Germans, these ice-free ports were a strategic advantage, especially in shipping out the rich iron ore from northern Sweden.

One of Norway’s war heroes was an old commander of Oscarsborg Fortress at the head of the Oslofjord. He had only a few green recruits at the fort on the foggy night of April 7, 1940, when he spotted three German warships enter the fjord. He tried to contact the leaders in the government in Oslo center, but all were asleep. The commander had no other instructions; so using old-fashioned weapons, more in the fortress for displays or for training purposes, he had his young recruits fire on the German flagship, Blücher, and, miracle of miracles, they sank it with all the German leaders and the main occupation force aboard. They also damaged the other ships, which then turned around and fled the harbor. Of course, this action did not stop the German invasion for long, but it gave the king and the government enough time to go into hiding in the surrounding forests (and eventually go into exile in Britain) and for people to haul all the government’s gold out of Oslo and into hiding in the mountains. (We drove by the section of the fjord where the German warship had been sunk.) The Germans occupied Norway until 1945, when Russian and other Allied troops defeated the remaining German troops. Norway had some of the fiercest resistance forces during the war and managed to help many Jews escape into Sweden.

After the war, it made sense that this country ended up developing one of the most successful socialist, welfare states in the world. After all, they had a history of egalitarianism, which included both men and women, and they had a fairly homogenous population. There is a famous quote by a Dane, N. Grundtvigin, but it is known and accepted in all the Nordic countries. It is almost their motto: “We will have made good strides in equality when few have too much and fewer have too little.” Scandinavians have probably come closer to achieving this equality than anyone else.

But returning to my quick romp through history, Norway was still dirt poor, relying almost entirely on fishing for their livelihoods (still to this day their second most important income source). However, in 1969, Norway hit the international Jackpot—they discovered oil and gas in their territorial waters of the North Sea—indeed, so much oil and gas that the reserves rival those of other big oil producers in the world. Not only that, the Norwegians have developed enough water (they have a lot of waterfalls) and wind turbine power generators so that everything (except cars) is run on electricity, including all their heating needs. They don’t need dirty coal, and they don’t even need their oil and gas. So they have ended up making so much money from oil and gas exports (which are heavily taxed by the government) that the income now pays for much of their welfare benefits. And the folks in charge of the Oil Wealth Fund have been wise enough to invest it carefully and spend it frugally. It is an increasing endowment that can not only pay for their current needs but can pay for the welfare programs and all the pensions for several generations to come. Banking against the day that the oil reserves will run out, they have invested in over 8,000 companies and enterprises world-wide. They have diversified wisely.

What is the result of this amazing resource on these present-day Vikings? Today Norway is one of the wealthiest countries on earth. There is almost no poverty. Almost everyone has a high standard of living. Anyone who wants a job can get one, and the salaries are high. They get 12 months of paid maternity leave; they get 5 weeks of paid vacation per year; they get liberal health care; they get free education through college; they get liberal unemployment and disability benefits; they get liberal retirement pensions. Many people have second, vacation homes, usually isolated in the mountains and fjords. Many drive nice cars—we saw a lot of Mercedes and Porches. Yes, they pay high taxes, but not so high as one might expect, not so much higher than the tax rates in the U.S. But they do pay high sales tax on most everything, including food. Because of the high sales taxes, gasoline costs about $8 per gallon (in American money); taxes on alcohol and cigarettes are extremely high, but that has been done by the government in part to try to bring down the rate of their usage. The cost of living is exorbitant—for everything—meals, clothes, entertainment. But the wages are also high. We talked to several Swedish women working in stores and restaurants who have come in from Sweden because the wages are so much higher in Norway. Imagine that: Swedish workers (not exactly from a third-world country) coming in to take the jobs that Norwegians no longer want to do. We found that waiters and store clerks typically make around $50 an hour.

We learned that they have an unusual way of handling housing needs, at least in Oslo. The government owns a good share of the housing, and a person does not rent from month to month nor does she or he usually buy a house. Rather she buys a lease—the right to rent and live in the place for perpetuity. In fact, when one dies, one can will the lease to one’s children. But the “life-long” renter is not allowed to sub-let the apartment or home to anyone else. So, I guess it is the equivalent of owning a home and paying a rental on it forever, but it also gives one total security in having a place to live and to pass on as an inheritance. Now isn’t that a different kind of ownership?

All this sounds great, don’t you think—a relaxed, comfortable life style? But here is the downside. Many observers think the Norwegians are becoming a lazy people. They now tend to take off from work about mid-day on Friday. They don’t like working long hours in the day or taking work home on weekends, and the mean retirement age is constantly decreasing, now at about 63 years. They have virtually every modern convenience one can imagine, with a standard of living that is easily as high or higher than in the U.S., but, what with the huge oil income, they don’t really produce much. They tend to work to be working, but they don’t seem to be driven to get ahead or make a difference. Their egalitarian attitude tends to encourage everyone to function at the same level, to not stand out and see oneself as better than anyone else, to keep one’s head down--which for many Norwegians is difficult to do. Beth and I were utterly taken by the number of tall people, many men hovering around 6 feet 6 inches or taller. I mean, why are these men wasting their time playing soccer and doing cross-country skiing? They should have professional basketball teams. In fact, why weren’t they the ones who invented basketball? And in terms of not standing out, they tend to dress like most everyone else in the U.S. and Europe. If you took a bunch of Norwegians and mixed them in with a bunch of Americans in Boston, you probably couldn’t tell who was who—well except for the tall Norwegian men and the beautiful blonde, blue-eyed Norwegian women. But they’re all wearing the same sneakers and jeans and talking on the same cell phones. (You may notice that I digress from time to time. I guess you will just have to learn to live with it.)

Anyway, back to what the modern Norwegian has become. Many observers do worry that despite their passion for outdoor sports and exercise (everyone hikes and does cross-country skiing and is outdoors all year round), they may be growing soft (at least mentally) and losing a driving edge. Another aspect I noticed that doesn’t seem to go with their modern-day egalitarian concern for others is their seeming lack of concern for the environmental impact they are having as a country. Sure, they are prime users of alternative, renewable energy sources, but their oil and gas production is not abating. They don’t tend to be a country that is strong on reducing global warming. After all, just like in America, that is in conflict with their main source of income. And we discovered another inconsistency. They are one of the few countries that still hunts whales and sells them for their meat as a delicacy (served in several restaurants we visited, which we refused to eat). Japan tries to excuse the practice of whale hunting by saying it is part of their cultural tradition (I guess just like cannibalism and slavery have been part of someone’s cultural tradition) and that justifies it. Norway doesn’t even try to justify it. They just hunt whales. They do claim that they only go after Minke Whales, which are not on any endangered species list, but come on—why do we need whale hunting in this day and age except to meet the taste whims of some very entitled people?

And perhaps the most troubling problem of all in modern-day Norway is the high alcohol consumption despite the government’s attempts to control its sales (similar to the other Nordic countries). Norwegians tend to not drink much during the week, but on weekends they binge drink and get tied up in “lost weekends.”

What else did we learn? As in most European countries, the influx of a lot of middle-eastern and north African immigrants is threatening Norway’s attitude of accepting everyone as being “all the same, homogeneous, and equal.” How they and other countries handle this challenge is still up in the air.

How did we learn all this stuff--or did we just make it up? Well, first, during our vacation we went on five short tours each handled by a most knowledgeable and accommodating guide—one in Oslo, one in Bergen, one in the Lofoten Islands, and one to some northern fishing villages (more on those areas later). But perhaps we learned most from our good friends, Jasmina Burdzovic and her husband, Orhan Hajdarpasie, whom we spent time with in Oslo at the end of our trip. To explain, both Jasmina and Orhan are originally from Bosnia and were refugees to Turkey, though they didn’t know each other. Then Orhan went to live in Oslo and has been working at the University of Oslo. Jasmina immigrated to the U.S. and became a U.S. citizen. She was a graduate student of mine at Brandeis University and, after receiving her Ph.D., was a professor at Brown University for some time before moving to Oslo, where she met her husband. (Jasmina and I have remained close friends for 17 years now.) She has an important job heading up a research center that studies alcohol and substance abuse in Norway and informs those making policy decisions. So Jasmina and Orhan were for us a combination of informed, emotionally ingrained insiders and objective outsiders, an ideal combination for understanding current-day Norwegian life styles and the pros and cons of Norwegian culture.

Jasmina told me a story that she thinks captures some of the differences between Norwegian social life and that in the U.S. She has attended several Norwegian birthday parties for adult friends, parties that to her seem to be handled more on the level that one would expect for a young child. The host makes cute decorations; they sing cute popular songs, often with simple lyrics made up to say how wonderful the birthday person is, much like kids’ songs. Then everyone goes around and says how wonderful the birthday person is, but each repeating quite trivial comments, such as, “Bjorn is such a nice person; he always smiles; he is kind to us; we like him so much; he is so smart.” She said, it made her want to scream, and she longed for the meaty sarcasm and edgy fun of American repartee and celebrations that generally end in a roast of the honored guest. It made me think of a few birthday celebrations that we have attended in the Boston area for Beth’s “Irish” relatives. They were edgy roasts, with people constantly quipping back and forth and telling funny stories and knocking each other in a good-humored way. I have never laughed so hard as I did at those parties. Jasmina said she misses that biting humor, that edginess and sarcasm in conversations that one experiences in the U.S. and in other countries (certainly in Ireland), but not so much in calm, polite Norway. It reminds me of a book I once read many years ago. The title was Scandinavian Humor and Other Myths. As one Norwegian said about the book, “It’s so funny I almost laughed out loud.”

And speaking of books, whenever Beth and I travel to some foreign country we try to pick out at least one book each to read that is in some way connected to or appropriate for the country. For this trip Beth read the Norwegian author, Karl Ove Knausgaard’s book, My Struggle (vol. 1). I read Michael Booth’s The Almost Nearly Perfect People. In that book he describes each of the five Nordic countries in order and uses many examples, interviews, and research to try to make sense of their life styles and their positive and negative aspects. It is written in a snide, somewhat sarcastic style with a lot of funny anecdotes, but it is highly informative. Jasmina and Orhan believe he nailed the Norwegians in his section on them.

Ok, so I have been going on about Norway, but I haven’t provided anything resembling a travelogue. Let me try to make amends. I will divide this part into four sections that match the course of our trip: Oslo, Flåm and Bergen, Our Cruise up the Coast, and The Northern Edge of Europe.

Oslo

The first thing that struck me about Oslo was how far outside the city the airport was (almost an hour’s drive from the city center), and, although it did allow us to pass through beautiful forested and rolling fields of hay and grass, as green as any hills and fields in Ireland (and that’s green), I wondered why they had located it so far out. (That was also the case with the airport in Kirkenes, far off to the north, near the Russian border.) I can only surmise that the plan was to avoid pollution and noise over Oslo and even over tiny Kirkenes.

We stayed right in the center of Oslo, which made it easy for us to walk about. Though Oslo sports some old sections with narrow, cobble-stoned streets and picturesque old buildings, it is indeed a modern looking city that seems to be under massive new construction. Supposedly, it is the fastest growing capitol city in Europe, and perhaps, along with Switzerland, the most expensive place to live. Right across from the University of Oslo on Karl Johann Gate, we watched a sidewalk artist create a most realistic sand sculpture of a yellow lab. We stopped to watch and listen to some Hare Krishna dancers in their saffron robes (I thought they had become extinct), and we watched another dance troop (actually anyone could join in) doing swing dancing and jitterbug to old fifty’s songs.

We visited the new Opera House, a prototypic symbol for modern Oslo, sticking up on the banks of the end of the inner harbor like a white and shiny iceberg in the water. The story goes that when the Opera House was completed and they held their inaugural performance, they got every person who had anything to do with its construction, from architects and supervisors to city planners and engineers to construction workers, painters, and janitors to come on stage and sing a final chorus. Everyone joined in whether they could sing or not. They even rehearsed beforehand. That just seems so Norwegian, putting everyone together in a project and celebration, regardless of station in life.

We learned of a new tradition (or fad) that has sprung up in Oslo. Friday night is now seen as taco night, and most everyone has tacos for the evening meal. Where did that come from? We did find one great sign in front of a Mexican food restaurant. See what you think.

This might be as good of place as any to talk about our meals in Norway. We were expecting the food to be predominantly seafood (true) and quite bland (false). Whether in Oslo or Flåm or Bergen or on our cruise, we had most wonderful meals—seafood in its many varieties—salmon, arctic char, trout, halibut, cod, king crab, mussels, caviar—spectacular sauces, beef and lamb, delicious soups and deserts, abundant breakfasts with a variety of charcuterie, cheeses, bread, and pastries, and perhaps best of all, present at almost every meal, lingonberries, fresh or in sauces and jams. Beth in particular seemed to live on lingonberries. Because the sun stayed out until late (or never set when we were above the Arctic Circle), we often ended up eating late at about 10:00 or 11:00 at night. We enjoyed one particularly memorable late-night dinner in Oslo along the Strand at Aker Brygge (dock), where we enjoyed a most tender reindeer steak and reindeer goulash (and of course lingonberries) amid the high-priced, modern buildings, clubs, and apartment complexes overlooking the boats and harbor.

Although most everyone dressed as they would in the U.S., we learned that Norwegians all have traditional clothes, collectively called bunad. Apparently each woman (and many of the men) owns her own bunad, specific to her area of Norway. These dresses are elaborately sewn and can cost in the neighborhood of $13,000 each (American money). So, though Beth was eyeing them in several stores, she certainly was constrained from buying one. Do the Norwegians ever wear them? Well, apparently on their national day on May 17, practically everyone—old and young--dons them for the many festivities. They also wear them for many dress-up occasions, for example, to attend weddings or special concerts.

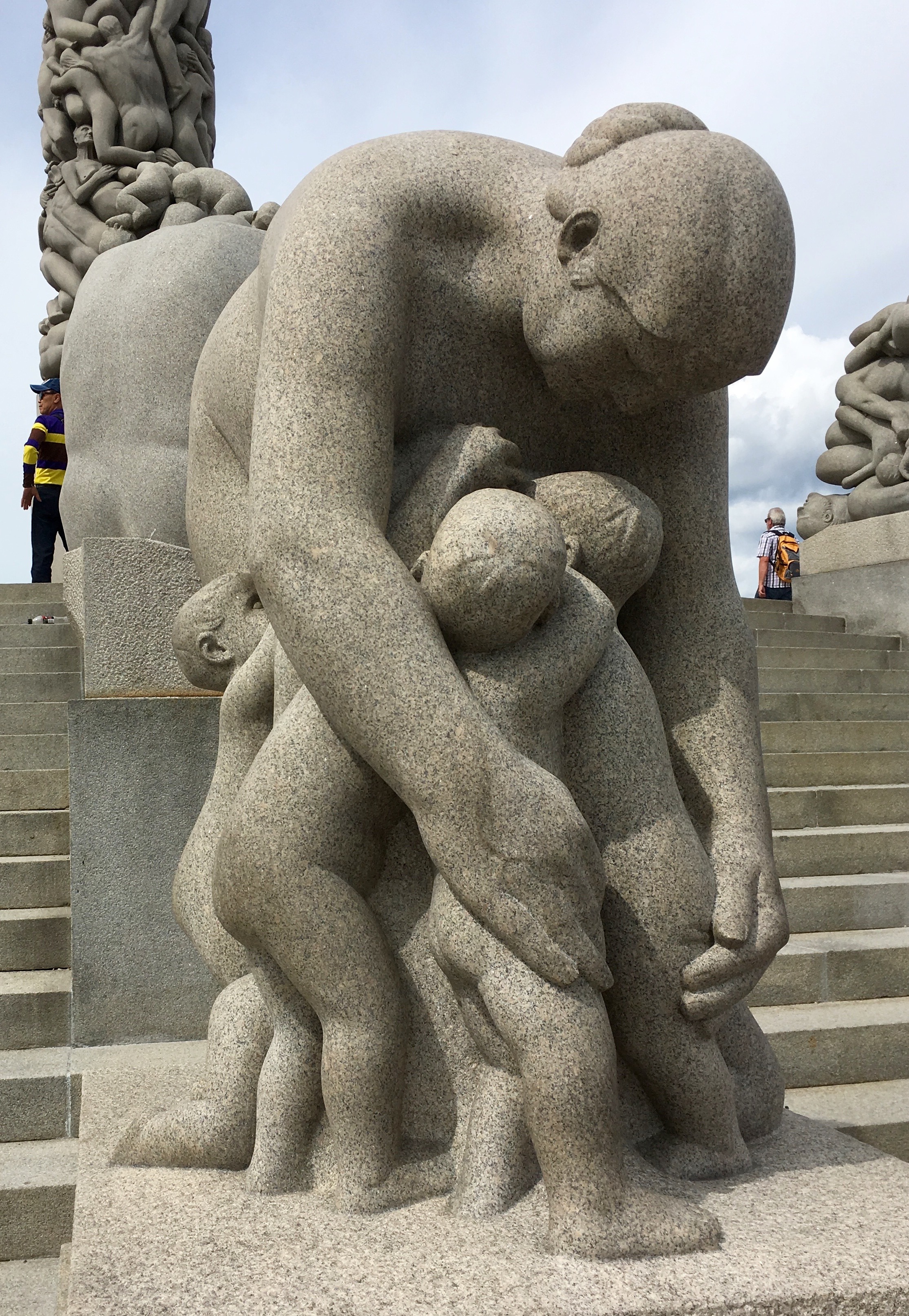

Perhaps the highlight of our sightseeing in Oslo was a visit to Frogner Park and the Vigeland sculptures. Here is the story. Gustav Vigeland was a gifted, local sculptor who had the idea to devote his life to creating a series of outdoor bronze and granite sculptures of people in various poses and groups, mainly representing the different stages of life and the various relationships between people, particularly in families—between men and men, women and women, certainly men and women, and parents to children. Somehow a bureaucratic miracle happened--he was able to convince the government to fully commit to fund the project from start to finish. Even with the German invasion, the Nazis let the funds be provided to keep him sculpting through the occupation. Vigeland died in 1943 during the occupation, but his assistants were able to complete his works. The irony is that his own family relationships did not match his artistic ode to families and human relationships. He was apparently a philanderer who married much younger women three times and by his actions estranged himself from his own two sons. (Such often seems to be the case when comparing artists’, writers’, and composers’ personal lives to their glorious works.) In any case, I believe the Vigeland statues are a world treasure and, when viewed together as he intended, are indeed emotionally and aesthetically moving to an indescribable degree. View them in person if you can. (I have here provided some photos of some of them.)

Flåm and Bergen

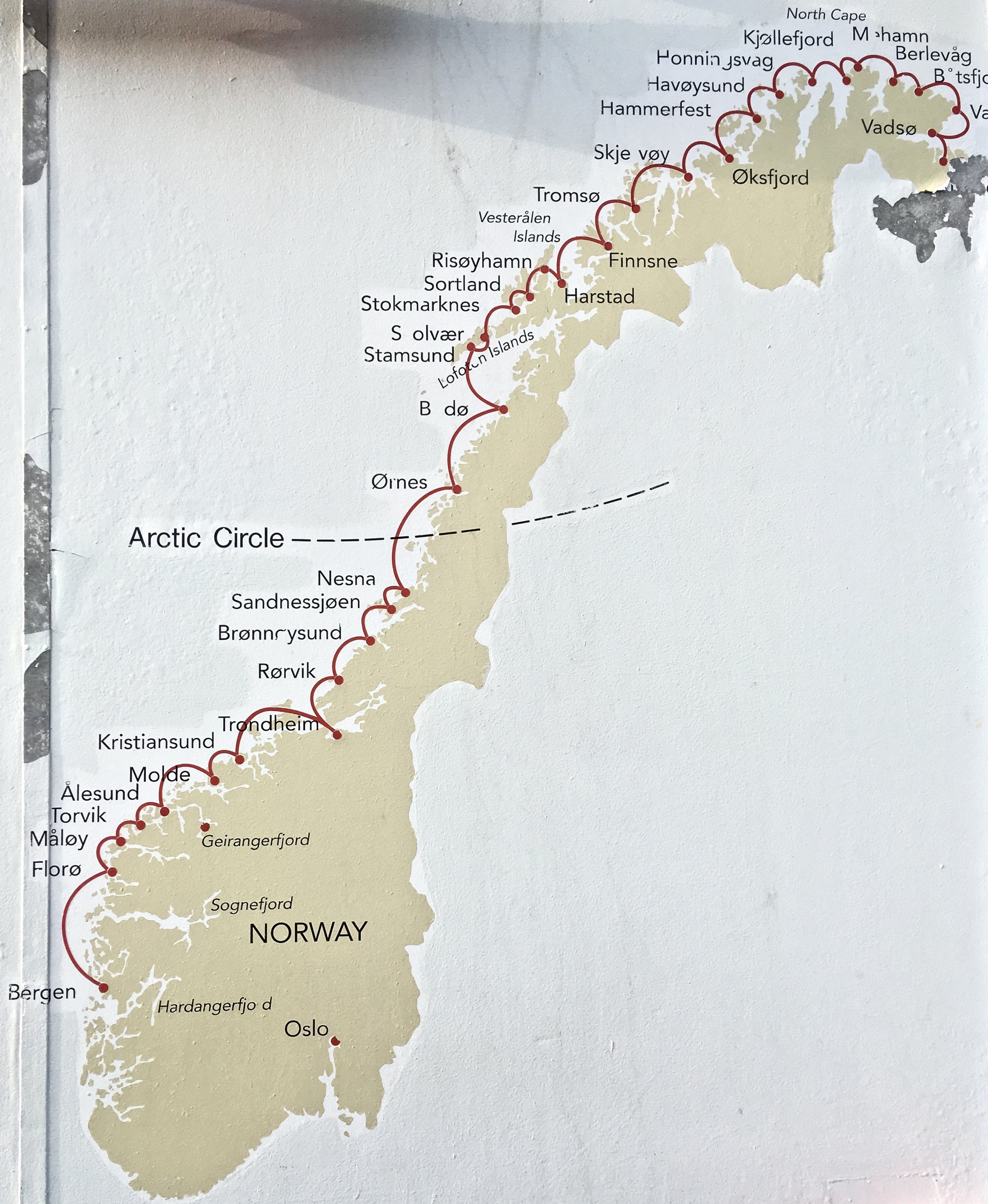

If you look carefully at the picture of the map that I have included, you can find Myrdal, Flåm, and the Aurlandsfjord as a finger of the Sognefjord, where this part of the story takes place.

On the train we took, which runs from Oslo up north through green hills, valleys, small villages, and into the high mountains above tree line, with their snowy, icy lakes, and foggy, cold rain and then cuts west and down out of the high mountains to Bergen on the coast, we realized that we were indeed on a movie set. The clue that gave it away was that they had cast a grandmother taking her two small granddaughters on a trip to Bergen to sit across from us. But the sham was given away because these folks were a little too perfect--exactly like we expected all Norwegians to look and act. By watching the girls interact with their grandmother I missed much of the beautiful scenery out the window. I almost missed it when weather-beaten backpackers and mountain bikers disembarked at an incredulous stop at what seemed to be the gateway to a cold, mountain death. Which to choose—watch the two cutest little girls the world has ever produced or the suicidal hikers and bikers go off to their last moments on earth?

But at the tops of the mountains before the train turned left for Bergen, in the town of Myrdal (if you want to call three houses and a railroad stop a town), we transferred to another train—the Flåmenbahn—an old, narrow-gauge train running steeply down out of the mountains, through tunnels, past waterfalls and narrow mountain valleys to the small village of Flåm at the end of the Aurlandsfjord. Wow, this scenery couldn’t be real; it had to be made with CGI. We checked into one of the two hotels in the village and then in less than an hour walked around the entire town. Flåm was surrounded on three sides by steep, green mountains, usually with their peaks covered by low clouds. Several waterfalls poured down the cliffs into a river that emptied into the fjord on the fourth side of the village. The setting was perfect, only marred by several tacky tourist shops, those annoying troll statues, and a huge cruise ship docked alongside the town and dwarfing it entirely. I was so happy when it pulled away. Our room was all rustic wood--wonderful, as were the meals we ate there. Across the river from our hotel, we found a flock of sheep of mixed breeds that seemed to be quite used to people coming up to talk to them. We also found a shop that purported to be that of the original shoemaker who had invented penny loafers and still sold these hand-made shoes there (too expensive for us). And, yes, they came with Norwegian coins stuck in them, which we learned was an old Norwegian tradition of putting coins in your shoes to indicate that you were well off.

In the morning we hiked up a narrow road on the side of the mountain and eventually reached some farmhouses and green pastures high up in a clearing above the town. As we continued further into the mountains now at the same level as the low lying clouds, we topped a rounded pasture that looked down through an opening in the clouds onto the other side, into another village nestled in a mountain valley. For some reason I didn’t think of trolls or Vikings but of Jack and the Bean Stock, which I thought I saw growing in the village and possibly providing a way for Jack to provide a suitable income for his widowed mother, even without selling the cow. Yes, this was a fairy tale.

The next day we boarded a hydrofoil ferry that took us on a five-hour trip down into the Sognefjord, past many small villages and isolated cabins and farms and then out along the coast and down to Bergen. We learned that this boat functioned like a commuter service more than a cruise ship. We made many short stops at the little villages along the way to let people on and off. Indeed, some of these villages were situated up against mountains so steep that I think there were no roads in and out and their only access was from the water. My favorite village was Balestrand (see map), where we would have liked to spend some time. What a magical ride. (I will probably want to say again and again, as I describe all the coastline and fjords that we traversed--so just consider it said here--magical.) We also discovered, as we observed throughout our voyage, that many of these steep mountains and valleys are U shaped indicating that they had been carved out by long ago glaciers.

Bergen is the second largest city in Norway. At one time it was the largest and most important because of its ideal location as a shipping port on the western coast. (And remember, the entire coast of Norway stays ice-free all year long, even in the dark winters, because of the Gulf Stream giving it warmth.) We loved Bergen. We decided that we wanted to move there, until we experienced rain and learned that it rains most of the year. Like so many other Norwegian towns, it is built around a sheltered harbor on the side of steep mountains, so the town center is located along the harbor and the houses then climb up the mountain and along the coast.

Bergen’s main street, along the Bryggen, sports 11 old wooden buildings in a row, looking almost identical to each other and fronted by a wooden walkway and dock. Other buildings, also built in a similar style to the 11 oldest buildings flank them. On closer look, these buildings tend to lean into each other, having seen some wear and tear and movement. What do you expect from all wooden buildings hundreds of years old? Actually, these current buildings are probably the third or fourth incarnation of the original homes, which were destroyed time and again by fires that swept through the town. Again, what do you expect when everything is built with wood and touching each other and all heated with open fires? The citizens are very much concerned with fires in their effort to preserve their old downtown area, and they have learned to put in plazas and open areas, which, though picturesque, were mainly done to provide firebreaks. Of course nowadays, they have elaborate fire-fighting procedures. Back in the day, they simply gave each family a fire bucket filled with water to keep handy in case of fire. But, think about it, if your house is going up in flames, what good will it do to throw a bucket of water on it?

Between and behind the old front buildings are wooden walkways providing access to lines of back buildings, each hosting various businesses and shops. Originally, each building and its line of back buildings formed something like a guild with one pole and hoist in front along the dock to hoist in fish and other goods arriving in the harbor and one toilet for all to use who lived and worked in that line of buildings. In back, each set of houses usually had its own kitchen and dining room for all to share. One of these original dining rooms now hosts the oldest restaurant in Bergen. To shop in this area is like walking through a maze of tunnels and narrow alleys. In fact, some of the named streets are so narrow that you would not think they deserved to have their own street names, but way back when, the streets were classified as one-horse or two horse streets, depending on how many horses could walk through abreast of each other. We did succumb and bought some most beautiful Norwegian sweaters in these shops, some from the woman who made them.

That first night in Bergen, at 10:30, in one of those front restaurants, we ate delicious arctic char and venison (and of course lingonberries). Then we returned to our room—a loft in the hotel, a building right on the water with boats moored in a narrow channel alongside. The next day, we walked by one old historic building that now hosts McDonalds. What were the town elders thinking allowing McDonalds into this beautiful, old building? Well, at least they prohibited McDonalds from putting up any permanent signs and constructing the golden arches (see the picture.) Across from the old row of houses, right on the water, is a famous fish market. Many small fish-monger stalls and fish restaurants are housed in one large permanent building and then in a row of tents. If one could keep eating, it would be tempting to just stay there all day.

We took the funicular up the steep mountain in back of the town for a superb view of the city below. Although the funicular is popular with tourists, it also provides a means for the locals to get to a maze of hiking and cross-country skiing trails up in the mountains.

Our Cruise Up the Coast

That evening we embarked on our cruise ship, the Trollfjord, named after perhaps the most mystical fjord we cruised in further north above the Arctic Circle. The ship is part of the Hurtigruten Line, and, once again, we discovered that it wasn’t only a cruise ship but a local transportation line up the coast. It made stops at many towns and villages along the way to let passengers on and off (and to take on local produce and fish—we ate fresh fish and locally sourced food when possible). (See the picture of the map of the coastal route of our cruise.) Whenever the ship docked for any length of time, Beth and I scampered off to walk around the local town. I won’t mention all these towns but will rather focus on our five favorites. Sometimes the stops would come at night, sometimes in the day, but keep in mind that it was always light because of the midnight sun, and up above the Arctic Circle, sunsets would usually last for about four or five hours. Because it never got too dark, we had to decide for ourselves to bring on the night by simply drawing curtains over our port window and declaring it now time to sleep.

We traveled the length of the Geirangerfjord, one of the longest in Norway, as well as the aforementioned Trollfjord, with its two or three houses located at its end, like a portal into another enchanted, lonely, and misty world. Who lives in those houses?

OK. Here are our favorite towns (from south to north) that we fell in love with and so wish we had had more time to spend in each one—maybe a month in each to get to know what life is like. First, of course was Bergen, then Alesund, and Trondheim, and then above the Arctic Circle, Stamsund and Svolaer together in the most beautiful Lofoten Islands, then Tromsø, and finally Honningsvåg and the two nearby fishing villages of Skarsvåg and Kamøyvaer—probably not household names for most Americans.

We arrived at Alesund early in the morning before most stores (or bakeries) were open. (In Norway, one should always be on the lookout for bakeries.) But we loved the layout of the curved main streets that looped around the curved harbor, the single grand canal that seemed to split the town as the town spread out onto a peninsula, and, of course the ubiquitous mountains behind it. Some time ago, Alesund had a fire that destroyed much of the town; so, much of it was rebuilt but in an art nouveau style. We wanted to stay here for a longer time.

Trondheim is Norway’s third largest city, with about 200,000 people and one of its oldest, founded in about 997 by Viking King Olav Tryggvason. It holds the Nidaros Cathedral, maybe Norway’s largest, which began as a Catholic cathedral, then became a Lutheran Protestant cathedral, and now is used by both religions (though few Norwegians ever go to church here or anywhere else in Norway). It houses a massive and impressive pipe organ, but we didn’t have the chance to hear it. Trondheim sports old wooden houses along its canal, though not so old as those in Bergen. We saw one funky, yellow kitchen that Beth thought she would like to rent (see picture). What do you think? Most of the city is filled with modern stores and buildings and looks like it could be a part of any modern city, despite the old sections.

Indeed, we observed that almost all Norwegian towns from large Bergen and Trondheim to those with less than a thousand people, huddled together on the cliffs and banks of the coast, are an even mix of old and modern. All have paved streets, usually a main (or high) street with state-of-the-art, modern stores of all kinds, and homes that seem well kept up and quite modern. Even folks isolated way up at the top of the world do not lack for modern conveniences and appliances. Just because they are up in the north way and isolated does not at all mean they are primitive or backward.

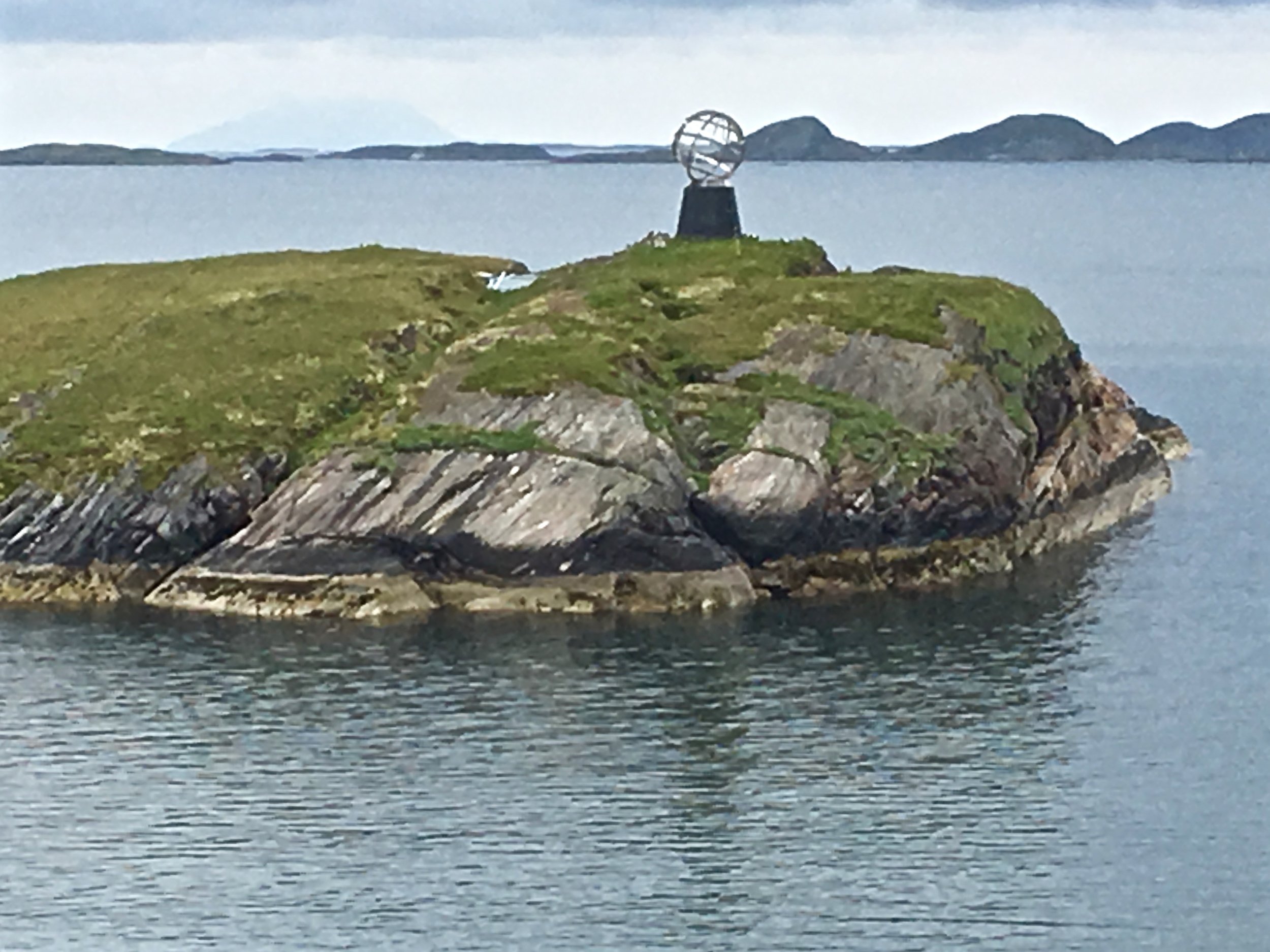

When we crossed the Arctic Circle just above the 66th parallel (by comparison, Boston is at about the 42nd parallel and Oslo at about the 60th parallel), we felt a bump in the sea. No, just kidding. But Beth and I made sure we were outside on the top deck to witness the crossing, at 7:15 in the morning. We were surprised that so few people had made it up to be there to witness it. We did pass a small island on which was a round globe sculpture (see the picture) indicating exactly where we crossed the Arctic Circle, which is the latitude at which for several weeks around the summer solstice the sun never sets below the horizon and for several weeks around the winter solstice the sun never rises above the horizon. The traditional ceremony for a person crossing for the first time into the Arctic Circle is to have ice poured down one’s back, but Beth and I ran away.

And then we came to my favorite place in Norway—the Lofoten Islands. This archipelago hosts several small fishing and farming villages and a lot of isolated homes (same old story), all surrounded by beautiful coasts, picturesque harbors, and, of course, towering, steep mountains. The Sami tribes originally had settled this area. Most of the islands are connected by bridges, tall enough for ships to pass beneath them and apparently quite scary in the winter when it is icy and windy. In the winter they illuminate signs when the bridges are swaying and too dangerous to pass. Cars have been known to blow off into the ocean. We disembarked in the small fishing village of Stamsund and caught a tour bus, which took us winding up through the town and along the coast and over to some other islands, past some rich farm land (for dairy and sheep and hay) and eventually into the main town of Svolaer, framed by mountains that looked like they had been carved by Norse gods. Now I had to be in the most beautiful place on earth, and we had so little time. I could live here—well maybe not in the winter, but of course the dark and cold and snow would be offset by the beauty of the Northern Lights. However, if you weren’t a fisherman, what would you do? I know, I would be an artist, but where would I sell my paintings? Well, where do I sell them in Massachusetts? Basically nowhere.

Along the way to Svolaer we visited an art museum and enjoyed the work of two artists who are famous (at least in the Lofoten Islands). I have included pictures of one painting from each of them—Kaare Espolin Johnson (the monotone painting of the fishermen) and Dagfinn Bakke (the watercolor of people enjoying the Northern Lights). We also visited a museum of what can be described as an old plantation. The owner had a magnificent home, furnished with the best in Victorian era furniture. He lived well; whereas all around him, living in sod-roofed shacks were the cod fishermen who fished and dried cod. He bought their fish at low prices and sold them around the world at high prices, then charged them rent to live in the houses he owned and sold them food and supplies from his store. So one way or another, the fishermen merely subsisted, while the money all made it back into his hands. (And so it goes.)

The Northern Edge of Europe

The largest town (actually a city) in the Arctic Circle is Tromsø with about 70,000 people. We loved the place, but we wondered, why in the world would 70,000 people decide to live up there at the top of the world almost. We never got a clear answer, but it seems as though it became a highly successful fishing town, year round, and the government built a big university there to serve the people of the north. People and businesses moved in, and this is how it ended up. We did see one troll that I admit I liked. (See the picture of the large graffiti troll painted on the side of a building.) We also ran across some stumble stones, just like one finds all over Germany and some other European countries. These are brass plaques placed in the cobblestone sidewalks in front of a house where Jews were arrested by the Nazis and taken away and killed. Each plaque gives the name, birthdate, and date of death of the person who lived there. (See the picture of some we found in Tromsø.) The idea is that as you are walking along not thinking about it, you stumble upon these plaques and they cause you to stop and think about those people who lost their lives. I think they are fitting tributes, and I think it is good for me to be “stumbling” upon them.

We stopped off at Honningsvåg at the 71st parallel, the northernmost capitol city in Europe. It is located on the island of Magelova in the area known as Finmark. Though it is the capitol for the entire region, it has only one gas station. They don’t list the price of gasoline. I mean, when you’re the only gas station, why bother? At the end of World War II, when the Russians came through trying to eliminate the Germans who were occupying this area, the Germans made a hasty retreat, but, I guess out of spite, before they left they burned down all the homes in the town. After the war, the townspeople had a contest to choose an architect and hired him to rebuild their entire town and all their homes. So, essentially, every home looked exactly like every other home. Since that time they have painted them different colors.

From Honningsvåg, we took a bus tour to the two northern most fishing villages in the world (above the 71st parallel). Along the way we saw herds of reindeer, most looking grand but motley, as this time of year they were shedding their white winter coats for their brown and gray summer coats. Reindeer run wild throughout Norway, but most of them are kept in semi-domesticated herds by the Sami and raised for the meat. A typical Sami family will have about 1000 reindeer, but we learned that one should never ask them how many reindeer they own. These animals are their wealth. It would be like asking someone, how much money are you worth? It’s rude. When I was growing up we always called these nomadic people in the Arctic the Laplanders, but we learned that calling them that is equivalent to calling African Americans or Native Americans some of the derogatory terms that have been used in American. It is disrespectful, and of course they don’t like it. How did it get to be like that? Well, it happens that the Norwegians (and their government) treated the Samis much as Americans treated Native Americans, taking away their land and freedom, forcing them into schools and punishing them for speaking their language and practicing their own customs. In the name of education they were trying to bring about cultural genocide, just as we attempted it in the U.S. In recent years, the government has tried to make amends and reverse all those prejudicial practices, and the old words associated with that time are no longer used. (I have included a picture of a traditional Sami summer home, which they still use from time to time.)

The first fishing village we visited was called Skarvåg. It was so far up there no trees grew. It was lonely and isolated, and only 40 people lived in the town and carried on their cod fishing enterprise. There are no longer any children in the town, thus no school, no grocery store, and no doctor. (With no children and essentially nobody moving in to this tight-nit, cooperative community, it probably won’t exist for much longer.) But it did have a restaurant, where we had waffles and jam, and the people did not seem to be living in poverty. I have included one picture of a modern looking home that looks quite middle class to me with a white picket fence, flowers, and lawn furniture. It all seemed so incongruous. But despite the desolate landscape the place was beautiful.

The next village, called Kamøyvaer, had a whopping 65 residents, but still no children, school, or hospital. This town had a large fish processing plant, which we toured. Drying cod, either hung from rafters or drying on wooden racks, could be seen everywhere. Apparently dried cod will keep for a long time, are easy to ship, and can be reconstituted. Strangely enough, this beautiful little town, isolated way up there in the north, had a wonderful art gallery, where we bought one painting done by Eva Schmitterer. It depicts a lone cabin up north with a spectacular sky. The interesting thing about her art is she does each picture as a collage from colored paper cut out of magazines (often from ads) and pieced together carefully. There are simply so many weird and wonderful artists in the world. (Check out the picture I included of the piece we bought, and see if you think it looks like a collage cut from magazines.)

At the end of the tour we headed up to the North Cape (see the picture of Beth and me). Here is truly the northern most edge of Europe. On the way back down to Honningsvåg, we passed a small, sorry looking beach that we learned they called the Copacabana and was the best sandy beach they had in all of Finmark. I guess for a day or two out of the year, folks go there to lay out on the beach. The guide said that the temperature was surprisingly warm—on a typical day, 21 degrees centigrade (that’s about 70 degrees Farenheit). We were skeptical. “Yes,” he said, “that’s 7 degrees in the morning, 7 degrees at noon, and 7 degrees in the evening.”

Our last stop was Kirkenes, close to the Russian border where we caught a plane back to Oslo.

In conclusion, in our family, some years ago we decided that we could all sound more sophisticated and educated than we actually were if we each learned to say one sentence in several languages. Then if we could fluently say that one sentence, we could impress people. (I’m not sure how well that’s working out for us.) In any event, the sentence we picked for our family is: “My pencil is big and yellow.” So for example, if someone asks me if I speak German, I say, “Mein Bleistift ist gross und gelb.” Well here it is in Norwegian: “Min blyant er stor og gul.” I am so sophisticated.

Wonderful, wonderful Norway, the almost nearly perfect place.